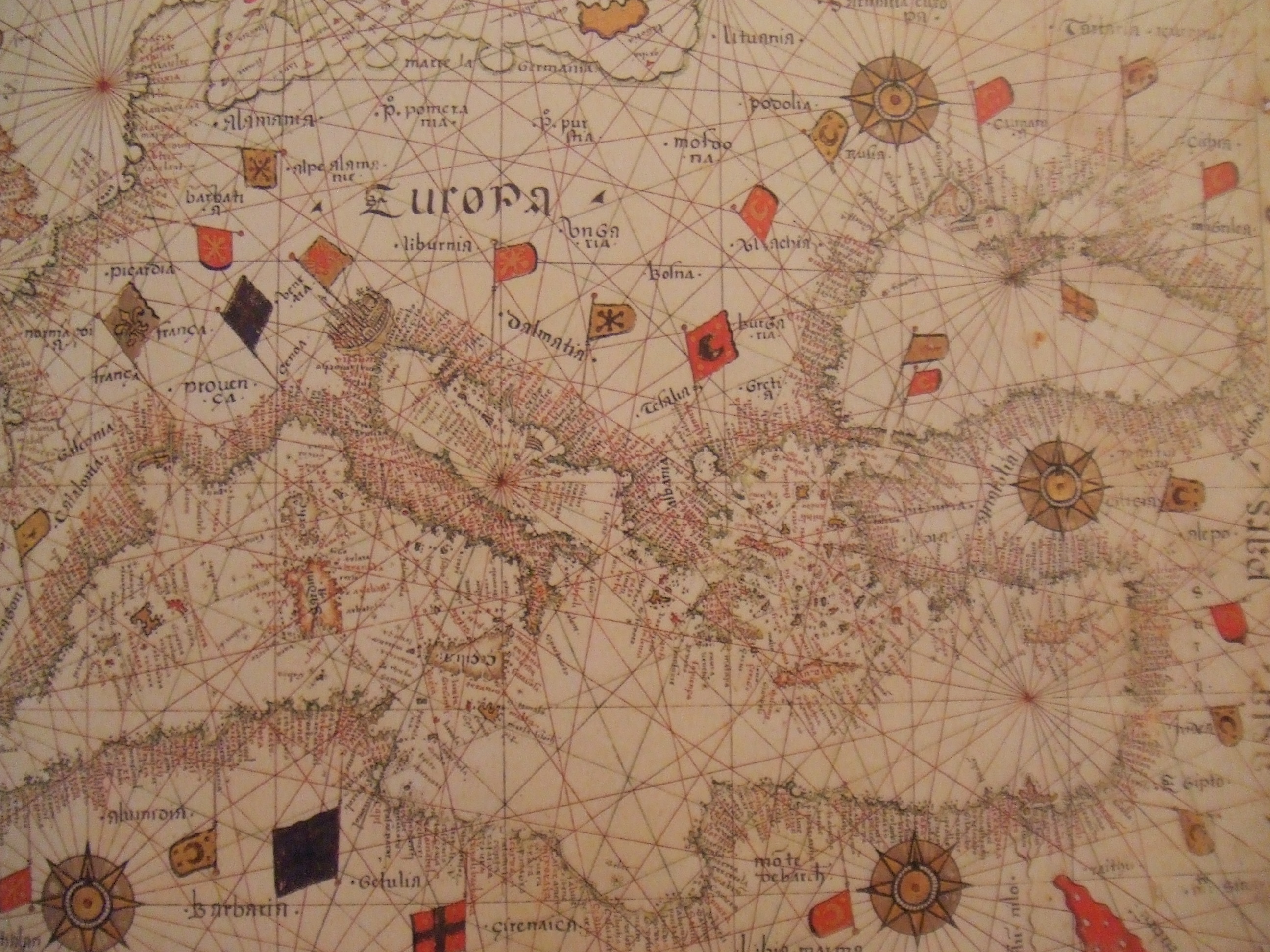

The city of Venice’s unique geographical location has meant it has always had a major maritime vocation over the centuries, with a special interest in Mediterranean trade, leading to its sovereignty, or at least hegemony, over the Adriatic Sea.

As a result, Venice set out to seize the monopoly in trade between Europe and the eastern coasts of the Mediterranean from its rival Genoa at the end of the 13th Century.

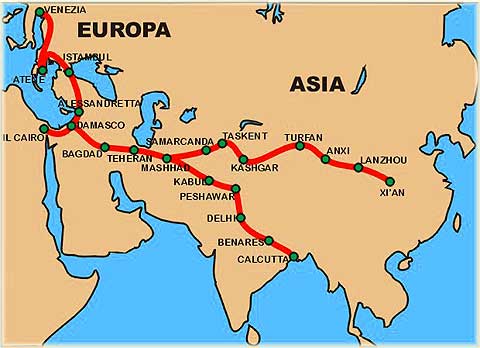

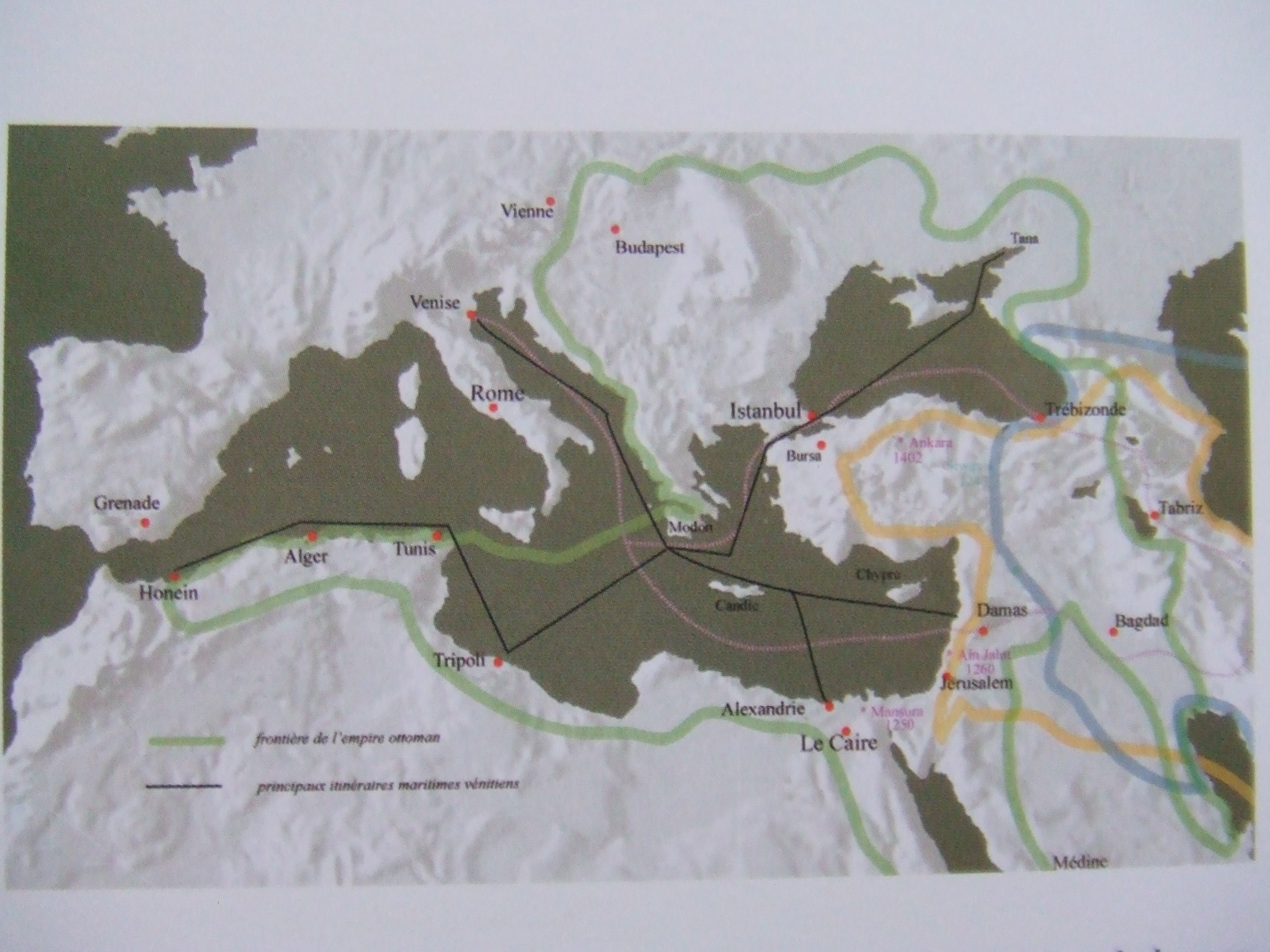

There were then basically two main trade routes: the northern route, connecting Venice to Morea Constantinople and the Black Sea, up to Azov and the Crimea, and the southern route, via Candia to Alessandria in Egypt or via Cyprus to the Syrian-Palestinian coastline (Alexandretta, Latachia, Beirut, Acre and Jaffa). Although ships continued to be the best way to carry people and goods throughout the modern age, the maritime route to Constantinople (originally capital of the Byzantine Empire and later that of the Ottoman Empire) was often replaced, albeit partially, by an overland route. Caravans of mules wound their way along the often hazardous roads from the coastal towns of Kotor and Split across the Balkans.

For some Venetian merchants in the 14th Century, however, the northern route did not stop at the Black Sea: with a special interest in trade with China, they continued along the "Silk Road" that crossed Central Asia to Catai, in modern-day China. Note that Marco Polo was not an isolated case: travel books, maps and detailed manuals in three languages (Latin, Turkish and Persian) prove that Venetians were frequent visitors to the shores of the Caspian Sea and on to the Asian towns at the end of this well-established trade route.

Less frequently, Venetian merchants travelled from Syria to the great emporiums of Baghdad and Basra throughout the modern age. However, these were indeed isolated cases, since Venice was mainly interested in the spice trade along the south-east Mediterranean coast, thanks to caravans run by Arab merchants for goods coming from Persia and India.

Although Venice never really enjoyed full monopoly of trade with the Levante (which always dealt with several trading nations at any one time), its leaders, the local administrations established in its domains by this “stato da mar” and traders scattered throughout the area co-operated over the centuries in creating a particularly effective trading system under the Byzantine Empire, during the Crusades, under the Mameluks and then under the Ottoman Empire.

Trade was so busy and important that it became a kind of economic model that anyone wanting to use the same routes was forced to recognise.When the Portuguese reached the Indian ports by circumnavigating the Cape of Good Hope and became privileged traders in the spice trade with Europe, Venetian trade entered a difficult period, although this state of affairs did not last for long. There were intrinsic limitations in the Portuguese route and then the Ottoman military power successfully closed the mouths of the Persian Gulf to the Portuguese, preventing further expansion.

In other words, the territorial unity of the Ottoman Empire guaranteed protection of the main trade routes across the Red Sea, the Syrian Desert and Anatolia to the Mediterranean coast, thus ensuring Venice continued to trade by sea, followed by its new competitors (the English, Dutch and French) at the end of the 16th Century.

The Levant was not, however, the only direction in which Venetian commercial interests lay: the Rialto market was frequented by several trading nations, including Germany over many years. German traders bought Eastern goods and organised their transportation with the Venetians to the North European fairs and markets.

As well as the major shipping routes to the East, Venice was also interested in trade with the so-called "Sottovento ports" . These were “caricatoi” (small ports, landing stages) along the west coast of the Adriatic with whom the Republic had enjoyed regular and profitable business relations, including the exchange of all manner of food ever since the times of Frederick II.

Moreover, as Mediterranean trade expanded in the 18th Century, there was renewed interest in the so-called "Ponentine" ports, such as Algiers and other towns along the Barbary Coast (North Africa), leading to the creation of a network of Venetian consulates along the North African coast.

Vera Costantini