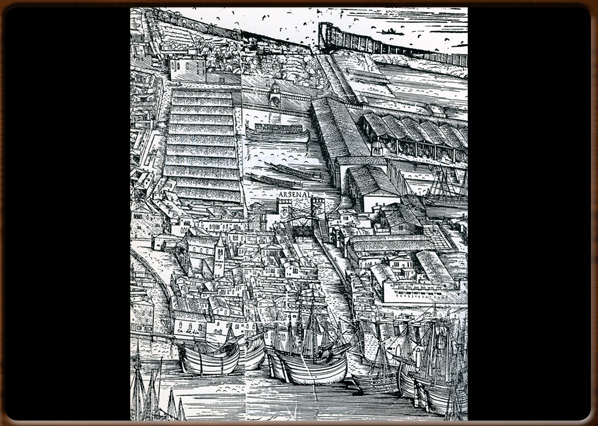

The Arzanà de’ Viniziani

The basis and foundation of this Republic, indeed the honour of all Italy…is the home of the Arsenale, a kind of Arx Senatus, i.e. fortress, bastion, barbican and support for the Senate…

With these words, Francesco Sansovino – author of the finest and most famous work on Venice, “Venetia città nobilissima” – mentions the Venetian Arsenale in 1581

.

But no description of the Arsenale can beat that of Dante Alighieri’s sublime verses (Inferno, XXI, 7-15): “As in the Arsenale of the Venetians / Boils in the winter the tenacious pitch / To smear their unsound vessels o'er again, / For sail they cannot; and instead thereof / One makes his vessel new, and one recaulks / The ribs of that which many a voyage has made; / One hammers at the prow, one at the stern, / This one makes oars, and that one cordage twists, / Another mends the mainsail and the mizzen”.

What Dante saw and so majestically describes was – at least for four centuries – the world’s greatest production site of the time, the beating heart of the Venetian maritime empire and the most impressive sight of intense industrial activity in the Middle Ages.

Its concentration of highly skilled shipbuilders (unbeaten in terms of expertise and number), meticulous organisation and amazing efficiency in how the production cycle was streamlined provide an incredible foretaste of the assembly lines of the Industrial Age several centuries later.

Still today historians of naval architecture admire the achievement and its methods are the subject of many studies dealing with the science of organisation.

The history of the city of Venice was closely identified with that of the Arsenale throughout its many centuries of supremacy and decline

. The Arsenale was the secret source of its maritime power and a fundamental part of the city’s legendary greatness, admired by sovereigns, scholars and scientists throughout Europe, from Henry III of Valois, King of France, to Henry VIII of England, from Peter the Great of Russia to Gustaf I of Sweden and, of course, from Dante to Leonardo da Vinci.

Its History

Venice celebrated the 900th anniversary of the foundation of the Arsenale in 2004: its legendary origins can, in fact, be traced back to 1104, under the rule of the then Doge, Ordelafo Falier

, even though the first certain documents mentioning the presence of a state-run shipyard in Venice in its current site in the sestiere of Castello at the extreme East of the city are from the 13th Century.

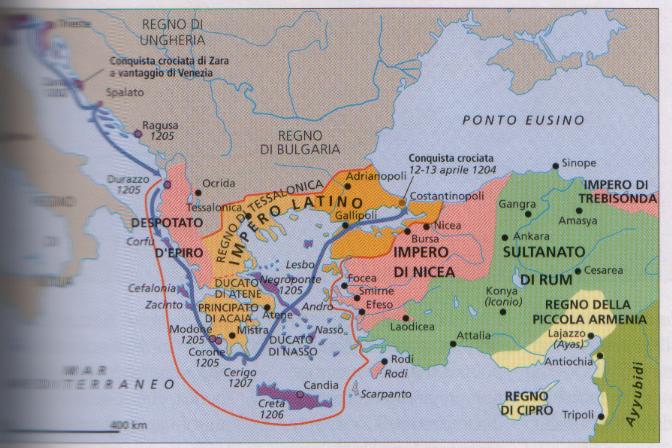

The Arsenale became the centre of the Venetian imperial power

and the logistic hub of the entire “Stato da mar” of the San Marco Republic when Venice, after the Fourth Crusade, realised the importance of maritime power, determined to consolidate the State fleet and so invested heavily in its shipbuilding.Docks,

"squeri", slipways, workshops for the construction, repair and maintenance of the fleet: an impressive complex

that still amazes visitors today, defended by natural and artificial canals and an immense belt of high embattled walls

running five kilometres around its perimeter and dominated by some fifteen towers that were manned day and night by guards to protect it from spies wanting to discover the industrial secrets behind one of the most outstanding fleets in maritime history

.

The immediate urban vicinity was also dependent on the great shipyard complex, with dwellings for the workers (the so-called “arsenalotti”), facilities (granaries, bakeries, bread stores) and other related and linked activities, traces of which can still be seen today in the fascinating place-names: Calle del Piombo, Calle delle Vele, Calle delle Àncore, Calle del Forno and Calle della Pegola (Lead, Sails, Baker and Pitch Streets respectively) and the Fondamenta della Tana and Campo della Tana (Embankment and Square of the River Tanai, now the River Don, whence the Venetians imported the hemp needed to make their ropes).

The first major expansion of the oldest area of the Arsenale (“Arsenale Vecchio”) was built in the 16th Century with the construction of the “Tana” (now the “Corderie”), a magnificent space used today for the “Biennale d’Arte” exhibition).

This was followed by the creation of new dockyard (known today as “Darsena Arsenale nuovo”), that increased the origin area fourfold allowing also for the building of all the mercantile galleys when Venice’s trade reached its zenith.

The Venetian Republic reached the peak of its economic, political and military power at the beginning of the 15th Century and the Arsenale – which was not just a huge shipyard, but also a highly equipped naval base for a permanent fighting fleet and a formidable gun production site – employed thousands of men with staggering output of up to two galleys a day.

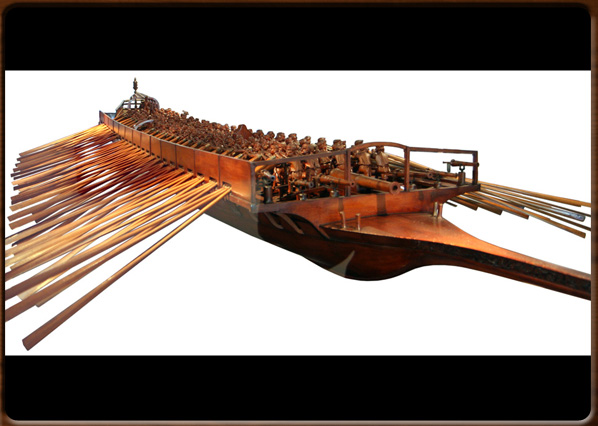

Later, the Arsenale specialised in the construction of fighting vessels and the Venetian galleys became a prototype for Mediaeval warships. One of the variations – the “galeazza”

– played a decisive role in the sea battle of Lepanto (1571): an early forerunner of the dreadnought, the powerful battleship conceived more than three centuries later.

The slow, yet unavoidable decline of the Serenissima started in the 1600s and dragged on into the 1700s.

When the San Marco flag finally stopped flying above the galleys in Oriental ports, the Arsenale also started to lose its supremacy and employment levels fell drastically, as did the shipbuilding activities, becoming obsolete in the face of more modern methods of shipbuilding adopted by the North European maritime powers.

Adding to this was Venice’s tendency to stand still, proudly resting on the laurels of its “mude” shipping line system, which still favoured the construction of large trading galleys, despite the fact that the trend was for freer navigation in individual, more agile ships and sailing ships.

During the annus horribilis of the Republic – 1797 - when under napoleonic rule Venice ceased to be a State, the Arsenale was fully destroyed by the French invaders and so it was not until the Hapsburg period of domination at the end of the 18th Century and the early 19th Century that shipbuilding started again.

Then, after a brief interlude of renewed French occupation, production continued until 1848, when, after Daniele Manin’s short-lived Venetian Republic, Austria transferred its shipbuilding activities to Istria.

Following the annexation of Venice to the Kingdom of Italy (1866), the Italian Royal Navy took efforts to breathe new life into the dockyard complex, balancing the need for rebuilding to meet modern shipbuilding technology with the desire to re-qualify this historical monumental complex.

Thus the Arsenale became the first industrial site in the newly unified Italy.

Nowadays, the basis for maritime power and major trade routes have greatly changed. The old Venetian Arsenale continues to preserve within its noble red walls traces of centuries of Mediterranean maritime history: the entire family of rowing boats (the wide and narrow galleys, the galleass and galliot battleships, light galleys, brigs and frigates); the family of merchant round ships (cogs, carracks, “marcigliane” and “buzi”; the family of sailing ships: galleons, frigates, trading vessels, xebecs, polacres, two-masted sailing ships, sailing brigs; and, lastly, the great innovations of the 19th Century: steamers, steamboats, dreadnoughts, torpedo boats and submarines (Venice Naval Museum).

Its organisation

Venetian historians traditionally explain the Republic’s supremacy not only on account of the excellence and constancy of the Venetian institutions, but also thanks to the social harmony that existed between the managing class and the working classes: in the midst of nations that were still barbaric and torn by feudal struggles, Venice had become a second “promised land” attracting people from all parts of the world and backgrounds. A place where the people and governing classes lived and worked in uncommon harmony.

The Arsenale was the paradigm of this interclass civic osmosis. It could draw on the unequalled expertise of its naval architects, of course, yet the real secret behind the titanic forge of merchant and battle ships described by Dante was its organisation, rationalisation and specialisation of the stages in construction adopted by the shipyard workers – caulkers, turners, carpenters, marangoni, oarsmen, blacksmiths, sawyers, rope makers, labourers, etc. – the famous “arsenalotti”, a body of men with extraordinary technical skills who passed these on from one generation to the next, together with the secrets of their craft and pride in belonging to a sort of militia at the exclusive service of the State.

The beating heart of the great factory, the “arsenalotti” formed a proper caste with its own guild register, benefiting from many envied benefits: an excellent salary, guaranteed lodgings and a safe future for their family and descendents. They were also the Venetian government’s most trusted guards. In exchange, they guaranteed absolute loyalty on the pain of the worst possible sanctions. In fact, a careless plotter or a disloyal mastro could end up paying for his misdeeds with his life or exile. To avoid theft and misappropriation, even the smallest tools and – believe it or not – nails were marked with the sign of the winged lion.

An expert arsenalotto, after some six or seven years’ apprenticeship, became a mastro (master), the most experienced and respected of which were then selected to become proti, responsible for designing and producing the ships, as well as the direction of all other connected jobs.

The four most important proti (responsible for the marangoni, caulkers, carpenters and oarsmen) formed the technical council of the Patroni or Provveditori (superintendents).

Another step in the career of these proti was to become a Stimadore (assessor), responsible for assessing the quality of the worker’s output, or an Appontadore (timer), responsible for absenteeism, quality control and time-keeping.

At the top of its organisation were the three Patroni ("Patron in Guardia", responsible for closing the warehouses and for the Arsenale guards, the Patron in Banca and the Patron Casser, responsible for checking the ships and deliveries, finances and accounts) and the three Provveditori, who had supreme control of the Arsenale, ensured relations between the Patroni and the Senate, proposed laws and exerted their authority in all strongholds of the Republic.

Finally, the top dog at the Arsenale was the Ammiraglio (admiral) who guaranteed what we would today call the management of “total quality” in modern business terms. Since he was given the title of "Magnifico” and stood next to the Doge on ceremonial occasions, one would be forgiven for assuming that he was of noble birth, but the Ammiraglio was in fact an ordinary worker who had managed to climb all the steps in the Arsenale career: an exceptional case of meritocracy.

The great originality of the production processes in the Arsenale, such as the osmosis of the managerial and working classes, was its true “power factor”. This consisted in a systematic approach and the concentration of each stage in the production process in the same place plus the meticulous care taken over each step in the process, even the choice of oak timber from the State forests on the mainland: this made for unrivalled rapidity and quality of the shipbuilding process.

Venetian maritime transport

Another decisive factor for Venice’s maritime supremacy was, in addition to the evolution of its shipbuilding industry, its organisation of shipping. Here the State adopted a series a defensive measures, thanks to privileges, subsidies and even armed protection.

Nowhere as in Venice was the shipbuilding industry so subject to the public sphere, and not just because of the war fleet – the only at that time entirely dependent on the State – but also because of its merchant shipping, which was often protected and subsidised with public funds.

The protectionist laws of the San Marco Republic handed the Venetian fleet the monopoly for all shipping for the Venetian merchants and the Port of Venice the role of an obligatory port of call for all mercantile shipping in the Adriatic. The resulting duties filled the State coffers and this money was then re-invested to produce economic and financial dynamism that brought further riches.

At the same time, foreign merchants were warmly welcomed and encouraged by dedicated infrastructures

(e.g. the Fondaco dei Tedeschi

and the Fondaco dei Turchi (warehouses/lodging for the Germans and the Turks).

Maritime trade also benefited from State protection thanks to the “mude”: regular convoys (initially following the routes to the Levant, followed by the Atlantic routes to Flanders and England) of rich merchandise using large galleys built in the Arsenale and hired out by the Venetian State, sailing with military escorts for protection against corsairs, pirati and competing powers.

This protection for its merchant navy, the crew and merchants influenced Venetian maritime law, even in the traditional onboard hierarchy. In fact, maritime law under Doge Zeno

(1255), for instance, was more attentive to the rights of the crew rather than the powers of the captain. Sailors were expected to report any breach of the rules by the captain.

In other words, the law made sailors responsible for the discipline of the captain to at least the same degree that the captain was responsible for the discipline of the crew.

The historical monumental complex

No foreigner passing through Venice would have missed visiting the Arsenale, whether king or emperor, merchant or pilgrim. The Arsenale, which appeared to the eyes of visitors as a majestic architectural complex, also stressed the greatness of the San Marco Republic (the “Serenissima”), tangible proof of its legendary “dominance”, maritime power and sound government.

Symbolic of this greatness is the magnificent Porta Magna

, the monumental entrance to the Arsenale, the first example of Renaissance architecture from the 1400s in Venice and still impressive today. A triumphal arch flanked by a pair of marble columns supporting Venetian/Byzantine capitals and crowned with an Attic pediment featuring the San Marco lion announcing that all in Venice – even the superb Arsenale and the Doge himself

, kneeling before the San Marco lion on the facade of the Doge’s Palace – is subjugated to the public interest of the State.Bucintoro” (Bucentaur), used to house the Doge’s ceremonial barge.

This was used by the Doge each year on Ascension Day to throw a ring into the lagoon as a symbol of the “sposalizio” (marriage) between Venice and the sea.

Other impressive structures linked to the shipbuilding industry include: the building of the Squadratori in the galleass canal where the wood was cut and the Corderie della Tana in the “New” Arsenale where hemp was kept and the ship’s hawsers were twisted, now a temporary exhibition venue (such as for the “Biennale d'arte”).

To the north of the “New” Arsenale, in the huge dock area called the “Arsenale Nuovissimo”, you find the “Gaggiandre”

, two enormous shipyards with particularly fine architectural details, built in the period 1568 – 1573, the design being attributed to Jacopo Sansovino.

Today this spectacular dockyard complex is partly used as the Italian Navy’s “cultural centre”, housing as it does the Institute of Maritime Military Studies and the Naval History Museum (in Campo San Biagio, close to the Arsenale), the perfect companions for this outstanding reminder of the greatness of Venice’s former maritime supremacy.

This museum is the largest in Italy and one of the richest of its kind in the world.

Located in the old granary building of the 1400s, the Naval History Museum

has exhibition space on five storeys and a total of 42 rooms, including the so-called “Ships’ Pavilion” in the old Oars Workshop serving the Arsenale.

There is also the twelfth-century Church of San Biagio, the church traditionally used by Venetian sailors.

The first three levels of the Museum contain artefacts bearing witness to Venice’s past maritime supremacy, its famous people and the arms and equipment onboard its ships. These include examples of authentic Venetian crafts and perfect scaled reconstructions of a trireme, a galleass (the Venetian battleship that helped win the sea battle of Lepanto in 1571) and the Bucintoro.

Other exhibits include models and objects from fishing boats and other typical vessels seen on the Venetian lagoon. These include, needless to say, the gondolas, with a whole room dedicated to these.

Then there are fine models of Oriental junks, relics, models and paintings of the old Maritime Republics and the Royal Navy. The Swedish room on the fourth floor is dedicated to the strong links between the Venetian Navy, maintained by the Italian Navy, and the Swedish Navy, built with input from the Italian shipbuilding industry.

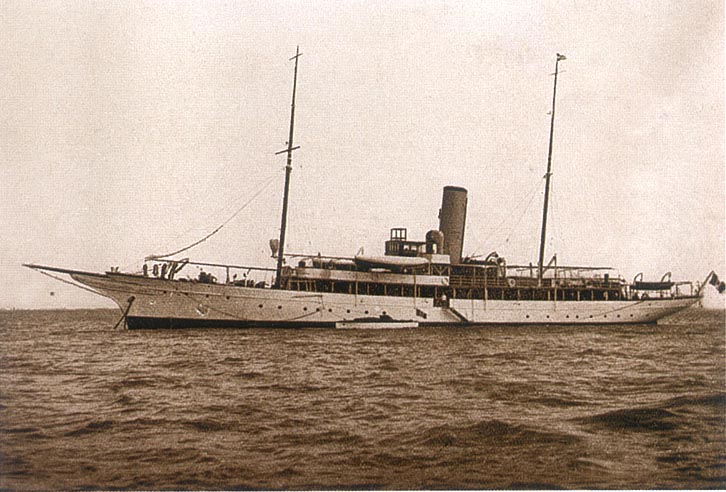

The “Ships’ Pavilion” in the old Oars Workshop – which for a period housed the Grand Council after the fire in the Doge’s Palace in 1577 – contains many genuine Venetian boats, military devices and a part of the engine room of the Guglielmo Marconi’s yacht, the Elettra

.

Arturo Faraone