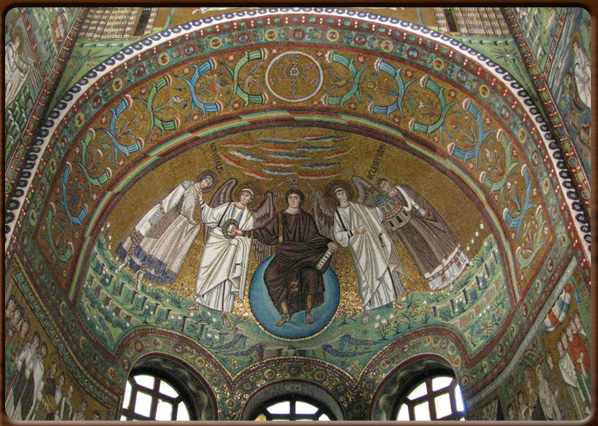

San Vitale in Ravenna, byzantinian mosaics, 5th and 6th centuries

Byzantinian and lombard Italy.

Charlemagne, illustration of 1858.

Holy Roman Empire.

No video

The first of the 118 Doges who marked the various periods in the history of Venice was Paulicio Anapesto. His election as dux, and not magister militum, the usual Byzantine title, was a clear sign of the city’s desire for autonomy.

In fact, however, the office of dux was also of Byzantine origin and depended on the Exarch of Ravenna .

The Doge’s functions were of both a civil and military nature. All the tribunes responsible for local authorities owed him obedience. Only the wealthiest citizens could become a tribune and so a sort of oligarchic aristocracy was formed. The tribunes were the only people that could hold the highest government posts and so, along with the highest representatives of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, determined the fate of the future Serenissima.

In 726-727 independence from the Byzantine Empire became a real possibility when the Venetian tribunes and clergy overruled the imperial appointment and elected by acclamation Orso Ipato as the new Doge of maritime Venice, backed by Pope Gregory II and in response to the measures on iconoclasm taken by the Emperor Leo III. The city’s desire to be independent of Byzantium became even stronger after 751 when Ravenna, the seat of Byzantine power in central-north Italy, was conquered by Astolfo I, King of the Lombards.

With the defeat of the Exarch of Ravenna, in 774 Pope Adriano approached Charles, king of the Franks and the future Charlemagne , for help. The Frankish army entered Italy and brought the Lombard dynasty to an end with the decisive siege of Pavia and the capture of King Desiderius. King Charles did not hide his ambition to seize Byzantine territories in the Veneto area and even planned to invade Venice with its troops. But diplomacy won out and an agreement was reached in 810-811 to avoid further bloodshed: Venice remained under Byzantine ‘protection’, while the Emperor of the East officially recognised King Charles’s title of Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire , which he had received directly from Pope Leo III at Christmas in the year 800.

Venice was thus not involved in the subsequent feudal organisation of Europe.

400 - 1000 - - rev. 0.1.7