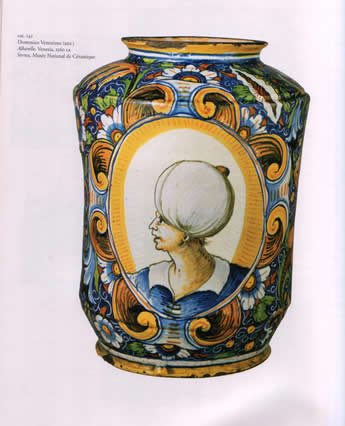

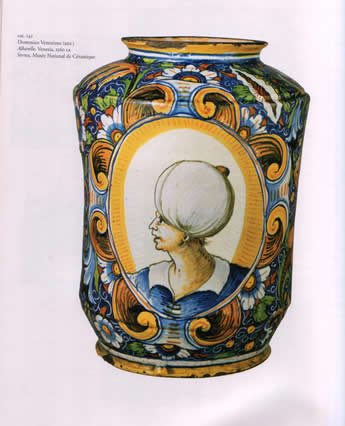

Plate.

Albarello, attributed to Domenico Veneziano, Venice c. 1560.

Plate in ceramic.

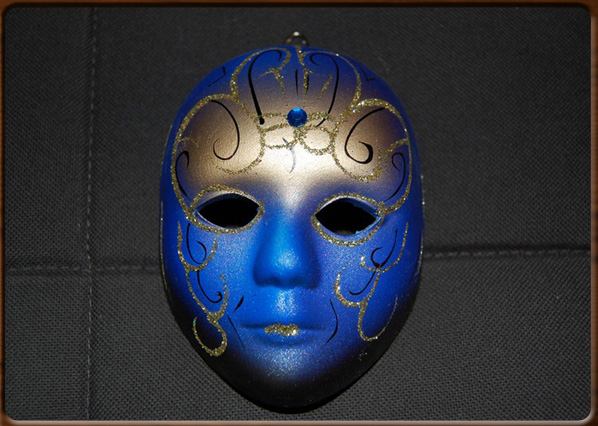

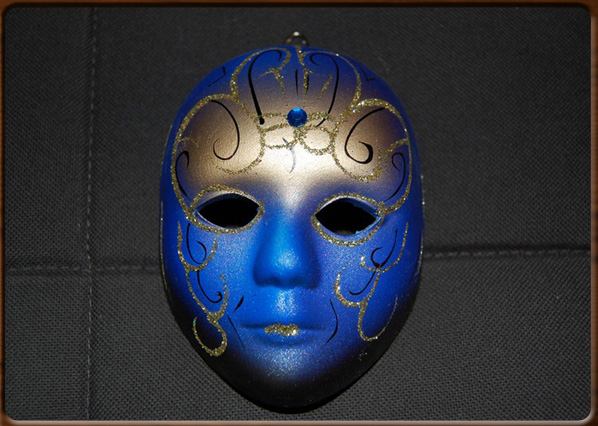

Mask in ceramic.

Small Statue.

No video

Venice was one of the first pottery centres in Italy: the oldest decorated plates date back to the first half of the 1200s, although several archaeological excavations have unearthed precious artefacts that date the first appearance of pottery in the lagoon area to the 6th Century.

In 1301, there were already so many Venetian potters that they formed a corporation and established the "Capitolare dell'Arte" of the "Scutelarii de piera".

Later, during the Renaissance, the Scutelarii adopted the name of "Bochaleri", though they also became traditionally known as the “Vasai del Leone” (the potters of St. Mark’s Lion).

The potteries were concentrated in the area of San Polo e San Barnaba. Indeed the remains of a kiln have been found in this area. The first Venetian dishes used two different glazing techniques deriving from two different traditions: [Byzantine] graffito ware and Islamic majolica ware.

In the 13th and 14th Centuries, Venetian pottery bore distinctive geometric plant motifs, either painted on or drawn by scratching.

At the end the 1300s, new forms and designs appeared in Venice, such as palmettes, lozenges and birds, a prelude to the more refined style of the mid 15th Century when human figures started to appear (mostly on vases, as engagement or wedding gifts).

The so-called “graffita conventuale” style became popular in the 15th – 17th Centuries, decorated with religious symbols introduced by San Bernardino. In the 1500s there was a vogue for plates decorated with the names and descriptions of local dishes written in the Venetian dialect.

Again, engravings of Roman ruins were very popular in the Veneto region in the 16th Century, thus leading to ceramic items decorated with such landscapes.

The majolica tradition was abandoned in the 1400s, then potters from the Marche and Faenza areas migrated to Venice and brought about a revival of enamel glazed production. Many workshops run by artists flourished and produced “wall plates” and prized majolica services depicting historical figures and scenes, now exhibits in museums throughout Europe.

The most popular genre was the “berettino” style of majolica ware, imported from by the Faenza majolica experts in the 1500s: pharmacy vases and ordinary crockery with a gray-blue glaze.

Output of Venetian pottery started to fall at the beginning of the 1600s and was in severe recession throughout the 1700s, despite the courage of certain Venetian entrepreneurs who imported kaolin from northern Europe and so introduced the art of bone china to Italy. The main reasons for this crisis were a fall in quality and, crucially, the liberalisation of trade in State goods, leading to the abolition of the corporation of the Boccaleri in 1806.

Indeed, while there were some thirty struggling potteries shops in 1773, just twenty years later only two potteries were still active in Venice.

1100 - 1200 - - rev. 0.1.13