Venetian gondolas.

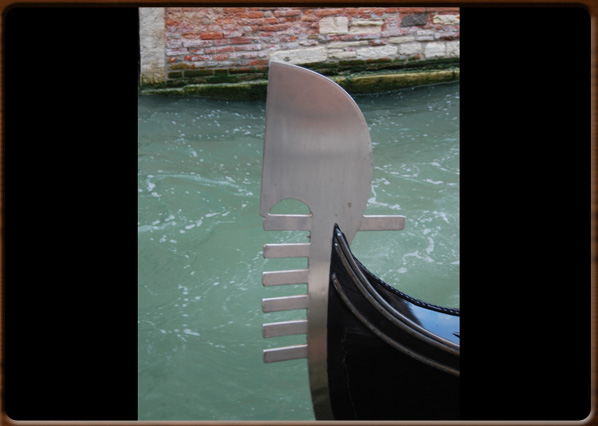

Iron at bow, called dolfin.

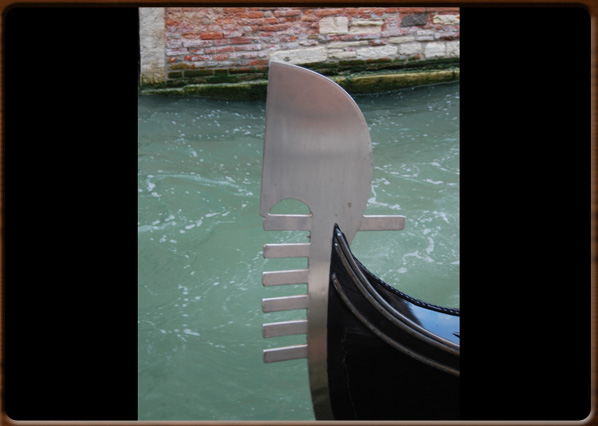

Iron at stern, called risso.

Venetian gondola.

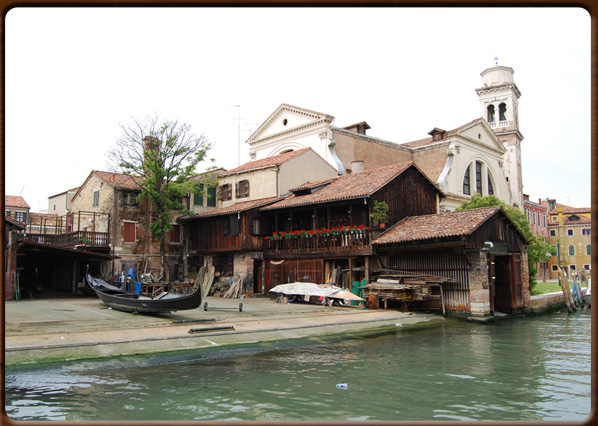

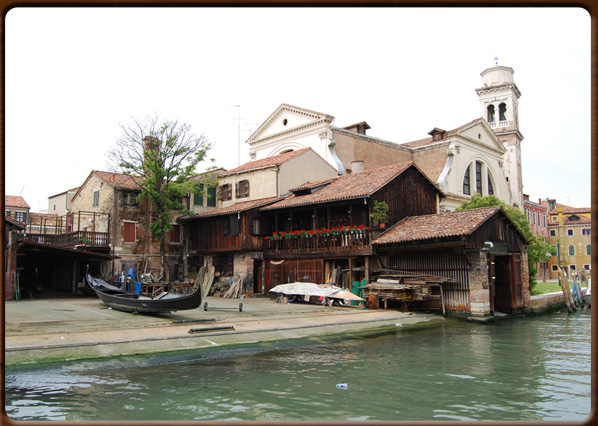

The 'squero' of San Trovaso.

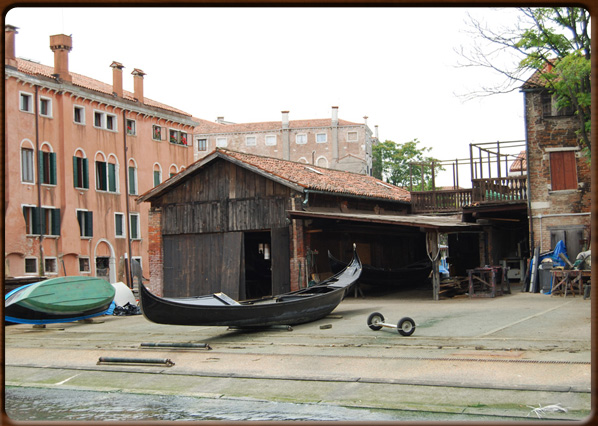

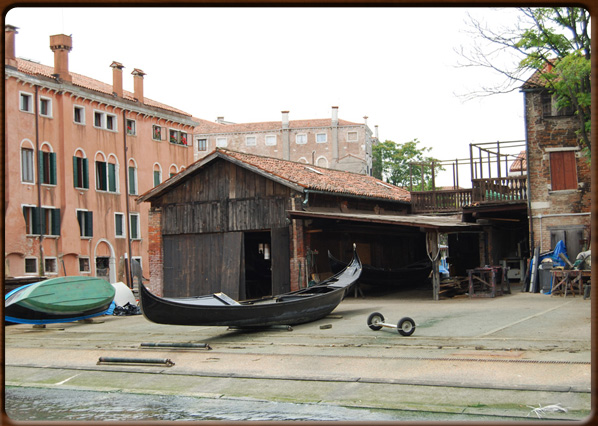

Deposit at the boatyard in San Trovaso.

No video

The Venetian gondola is believed to the most beautiful boat in the world and the universal symbol of the city of Venice. The beauty of the gondola lies in its elegant sinuous line and in the wonderful environment in which it moves, plus its unique construction: a vessel some 11 metres long and weighing 600 kg, the result of such an excellent construction technique that it is easy and light to handle by just one person using a single oar.

Origins and history

The gondola has undergone many changes over the centuries. The modern version is thus the result of a long process of evolution and adaptation to the varying needs of the gondoliers and the changing characteristics of the water. The history of the gondola and the history of Venice are thus intertwined.

The first records of a gondola date back to 1094 when the Doge Vitale Falier issued an official decree that excused the inhabitants of an island south of Venice from providing a “gondulam”.

Early records do not, however, provide enough details to let us reconstruct its appearance. It is only in the late 1400s and early 1500s that pictures and drawings appear with precise iconographic details. The vessel was very different from the one we see today, apart from the black colour of the hull, typical of all Venetian boats due pitch being used for water-proofing (although according to legend, black was used to mourn plague victims).

The gondola in the late 1400s was similar to other lagoon craft.

It only started to differ in the early 1500s when it started to be used mainly to carry low ranking passengers. Towards the end of the 1600s its shape began to resemble what we call a gondola today.

In the 1800s a few technical changes were introduced: an asymmetrical design that accentuates the curving and rising of the stern making it easier for the gondolier to manoeuvre it.

Until just a few decades ago there was a removable wooden cabin, called the “felze”, in the centre of the gondola. This was used to shelter passengers in the winter, but fell into disuse as it hampered visibility and so not suitable for tourists.

In fact, the gondola is now used exclusively by tourists. According to some estimates, there are approximately 500 gondolas in Venice today. A relatively small number if one considers that more than 10,000 gondolas circulated on the canals of Venice in 1580.

Symbols

Every detail of the gondola has its own symbolism, especially the metal parts, whose formal elegance is combined with practicality and usefulness.

The iron prow-head of the gondola, called “fero da prorà” or “dolfin”, is needed to balance the weight of the gondolier at the stern and has an “S” shape symbolic of the twists in the Canal Grande. Under the main blade there is a kind of comb with six teeth or prongs (“rebbi”) standing for the six “sestieri” of Venice. A kind of tooth juts out backwards toward the centre of the gondola, called the “risso di poopa” (literally, “hedgehog of the stern”) symbolises the island of Giudecca. Sometimes three friezes can be seen in-between the six prongs, pairing the sestieri, indicating the three main bridges in the city: the Rialto Bridge, the Ponte dell'Accademia and the Ponte degli Scalzi.

The Squero

The “squero” tradition is as old as Venice itself. The name comes from a tool, the square (“squara” in the Venetian dialect). Initially the squero was a place where all sorts of craft were built and repaired, from galleys to gondolas, large sea-going ships to small punts.

However, while still important, their business suffered when the Arsenal was built, as this became the focus for Venetian shipbuilding.

Over the years many squero boatyards disappeared or were converted as the demand for rowing boats fell.The few squeri that still exist in Venice today deal mainly in gondolas. Just a few skilled craftsmen still produce gondolas in these boatyards, the secrets of the trade being handed down from father to son or master to apprentice.

Each craftsman, called a “squerarolo”, works freely, guided by experience built up over the years.

It takes at least 36 months of practice followed by a final exam before a craftsman can become a “Maestro d’Ascia” (master shipwright).

Each squero has a sloping yard leading down to the water (an access ramp) that is fenced in on either side and with a “tesa” (a wooden building offering protection from the weather and used to store tools and gear) at the back. The “squerarolo” (shipwright) or owner often lives next-door or above the yard.

The oldest active squero in Venice is that of San Trovaso in the Dorsoduro district and dates back to the 1600s. It has an unusual shape, much like a mountain chalet, emphasising how the oldest and most renowned squerarolo families came from the Alps, especially the Cadore and Zoldana Valleys.

Construction and materials

The gondola has a unique asymmetrical design: the left side is 24 cm longer than the right, so that it always travels leaning to one side. It has a flat bottom making it suitable for very shallow water. Eight different types of wood are used for the 280 components making up each gondola. The only metal elements are the characteristic “fero da prorà” (prow) and the “risso” (stern).

Before starting actual construction of a gondola, the timber needs to be carefully selected. Eight types of wood are used for a gondola: oak, deal, elm, cherry, larch, walnut, linden and mahogany. After choosing the timber, which must be totally defect free, it is then seasoned for about a year.

Actual construction consists of five well-defined steps, carefully carried out with by few master shipwrights and squeraroli in business today. A gondola is said to be finished once the oars and oarlocks have been added. It takes several months (about 500 working hours) to build a gondola.

1300 - 1400 - - rev. 0.1.11