The transformation of the lagoon area into a state of growing importance during the last years of the Roman Empire and the early Middle Ages was a complex and long process .

It involved overturning the old status quo, turning a “marginal” area into a body that, within the space of just a few centuries, became one of the great European powers.

The first phase of development of the city and the Venetian state took place during some very unsettled times: the origins of Venice date back to the time of the Lombard invasion in 568, when the lagoons were still part of the Byzantine Empire, although the rest of Italy was experiencing the gradual expansion of the Lombard kingdom and then, in 774, the final conquest by Charlemagne.

Throughout this period, the northern Adriatic coast from Grado to Cavarzere (i.e. what would later become the Venetian Dogado ) continued to be tied to Constantinople in its role as a province, though this was in practice becoming more and more estranged from a capital that was irretrievably losing its importance in Italian affairs.

Centuries of subordination for the newly-fledged city of Venice, though it was also to its advantage to be dependent on a far-off power - and therefore less able to interfere – rather than on closer and more intrusive powers. There was a critical moment for Venice in the early 800s when Charlemagne fought against the Byzantine Empire and the lagoons were almost conquered by the French troops.

This would have led to Venice being re-absorbed into a mainland Western empire and a feudal culture and an end to its maritime development. However, thanks to the outcome of the conflict, Venice remained within the Byzantine sphere and so the whole of the lagoon area enjoyed a significant change in its status quo. In fact, the capital city of the Venetian province was first Aquileia, then Oderzo (both on the mainland), then Eracliana Cittanova (on the edge of the lagoon), followed by Malamocco (along the coast, towards the sea), before finally moving to the islands around Rialto in 810-811, where the city of Venice was slowly forming.

Constantinople’s sovereignty did not mean only important consequences and benefits on a political level: there were also economic, commercial and cultural advantages for Venice too. It was linked to a world that was far more developed and wealthier than the West and mainland Italy, thereby guaranteeing it belonged to a Commonwealth that would also ensure that the positive developments already underway would continue, especially increasingly greater degrees of autonomy.

Indeed, historians have always insisted on the importance of the freedom afforded by the original Dogado: the myth of its birth in wild deserted placed is based on this. If - as was claimed - Venice arose from nothing among the waters, free of any form of subordination, this involved the right to full and absolute independence.

In fact, the lagoons were an integral part of the Roman province of Venetia et Histria and thus included in the policy framework of the Roman Empire. Even in the 10th Century, Byzantium could still have legitimately sent a commission of inquiry to make sure that its distant province at the top of the Adriatic Sea respected its obligations (especially: the ban on trade with the enemy, the saracens).

Dependence on Byzantium gradually diminished, with Venice enjoying considerable autonomy, to the point that it was no longer seen as a subject city, but an ally. Its contributions in warding off the Slavs and Saracens in the 9th – 10th Centuries prove how it was gaining for itself a strategic importance in the Mediterranean, taking over the role of the Byzantine fleet.

The Doge, especially after the Lombard conquest of Ravenna in 751 was increasingly less representative of the power of Constantinople and increasingly the exponent of Venetian autonomy. This process was completed by the time of the great Doge Pietro II Orseolo (991-1009), who assumed the title of Dux Veneticorum et Dalmaticorum in 1000 (i.e. Doge of Dalmatia as well as of Venice ) after a successful sea battle.

Venice’s economic and institutional development grew at the same rate as its political autonomy. Venice had become a major link between various economic, political and cultural areas, connecting Christian Europe to the Byzantine and Islamic civilizations, which at the time were more developed than the West.

By the 9th and 10th Centuries the Venetian fleet was already free to travel throughout the Mediterranean: proof of this can be seen in the fact that the remains of St. Mark the Evangelist were stolen from Alexandria of Egypt in 828 by Venetian merchants who happened to be there, despite the fact that there were strict restrictions on trading with the Saracens. From that point onwards, the cult of St. Mark was the basis of the Venetian state’s ethical and political policies.

Early economic development was accompanied by improvements in the institutional structures that, in turn, gave shape to a strong state with some peculiar characteristics.

In the first place, the old dependence on Byzantium gave way to full independence and indeed, during the time of the crusades, the deviation of the Fourth Crusade led to the conquest of Constantinople in 1204 and the temporary end of the Byzantine Empire, being replaced by a Latin Empire of the East created and nurtured by Venice.

At this time the Venetian Doge even assumed the title of dominator (i.e. Lord) “of a fourth and half part of the Empire”, namely three eighths, the share allocated to Venice when the lands were split between the various Crusaders.

The Doge (i.e. the Duke) was originally the representative of Byzantine imperial power. This figure gradually turned into a symbol of autonomy and later the independence of Venice.

In fact, there was a period during the 10th Century when this office acquired dynastic connotations (under the Candiano and Orseolo families), but institutional growth subsequently coincided with a gradual reduction in the power of the Doge, with measures introduced to ensure the Doge was seen as the symbol of state sovereignty and to limit his powers greatly.

He thus became the living image of what really mattered, namely the State. Thus other institutional bodies grew in importance, alongside the Doge, from the 12th Century onwards.

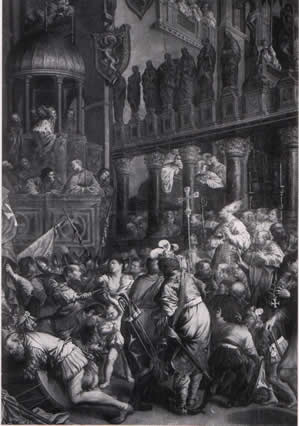

A key date in this process was 1143, when a “Council of Wise Men” appeared alongside the Doge Pietro Polani and his magistrates, responsible for “keeping order, the profits and the safety of the State”.

Almost simultaneously (in 1144), the term “Comune” started to be used, as in many other places in central and northern Europe. But the Venetian experience was quite unique, as can be seen by the fact that the top office (the Doge) was for life and not short-term (usually annual) which was the case elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the Great Council had replaced the old “Council of Wise Men” with regard to lawmaking and resolutions, while the more agile Lesser Council provided the Doge with specific executive functions. Other magistrate offices were introduced, such as the Avogadori di Comun, responsible for defending public rights and the law, and the Giustizieri controlling the growing Arts corporations.

The main bodies at this time also included the Quarantia (Council of Forty) – initially a consultative body and later the Court of Appeal and supreme judicial body – and, especially, the Consiglio dei Rogati (the Senate) which gradually became more and more important, finally embodying the true soul of the Venetian Republic.

Venetian oligarchy and its political/institutional system reached a turning point towards the end of the 13th Century when the requirements for access to the Great Council were defined. The aim here was to broaden participation in this, but in practice it fore-closed membership to this “club” by determining which families were eligible. Thus it is known as the “locking of the Great Council”.

In any case, whatever the actual intention, the sovereign Venetian hierarchy became hereditary, thus giving the state an aristocratic feel.

A strong mercantile culture was the distinguishing feature of both the aristocracy and the Republic that rose to imperial power in the 13th Century. The fortunes of Venice had always been linked to the sea and to trade.

Indeed, the ruling class in Venice was never ashamed of this fact, unlike other aristocracies on the mainland, who despised the ideas of using money and “trade” in the early/central Middle Ages, considering it a matter of low prestige (until, that is, the economic recovery, the rebirth of cities and the culture of city-states: the "bourgeois", in the real sense of the word).

Venice was way ahead of the times in this regard. For example, even as early as 828 the Doge (Giustiniano Particiaco) did not have the slightest problem in listing huge amounts of money invested in foreign trade companies in his will: real venture capital.

Trade, i.e. exchange and transactions between distant areas rather than actual production, soon turned the Rialto market into one of the top financial centres of the time and Venetian coins (especially the "grosso" silver coin at the beginning of the 13th Century and the gold ducato issued in 1284) were widely accepted .

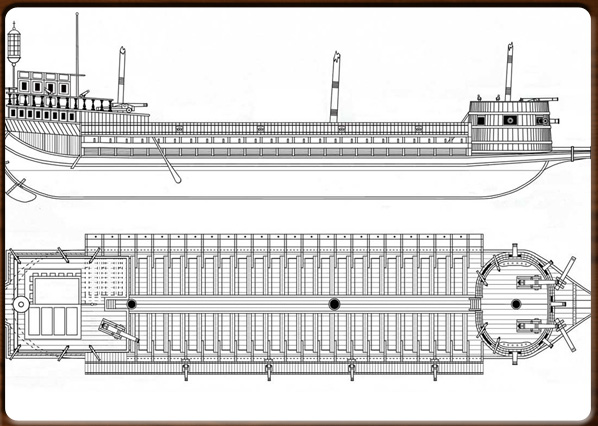

The Arsenale was easily the largest factory of the time and the Republic even considered it necessary to organize trade by means of direct intervention that proved to be very wise and effective. For example, by organizing the "mude" that regularly sailed to the Levant and along the coasts of the western Mediterranean and on up to England and Flanders. A functional combination of state intervention and use of public power and private participation.

This highly effective interweaving of public and private matters is another unique element of Venice’s long history, a city that knew how to ensure adhesion of its subjects without conflict.

Although apparently strange when one considers the oligarchic character of the state, this can be explained by its ability to conduct public affairs in a way that was broadly acceptable to the people: the logic of “good governance” that was almost a legend of the St. Mark’s Republic.

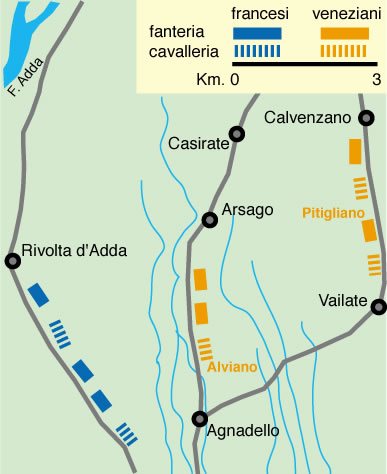

Of course, the strength of the state built up in the Middle Ages meant that it easily survived difficult moments over the centuries, such as in 1509, at the time of the League of Cambrai, when Venice managed to recover from a blow that many believed would be fatal with half of Europe at war and after the disastrous defeat of Agnadello .

The Republic’s strength was crucial at such times. This was supported by the widespread perception that personal advantages could be best guaranteed by a robust, well ruled state.

With this in mind (and without having to call into question any love of one’s country or other noble feelings that, if truth be told, do not really seem to be the driving forces of history), the very merchant-based culture of Venetian society led to a recognition of the connection between the common good and individual interests.

Of course, the Venetian environment and its organisation were extremely complex, articulated and often contradictory, but the overall system was able to operate and continue over the years, ensuring that the Republic lasted for about a millennium, its heart being a city that was one of Europe’s first and most important metropolises.

Today Venice is still an outstanding example of a “city” in the full sense of the word, even if it is now only part of a mainland metropolis, the brainchild of Italy’s fascist era.

Gherardo Ortalli