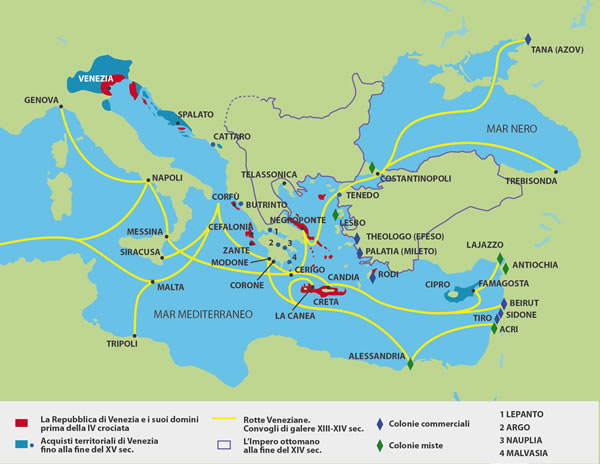

Management of uninterrupted trade with the other side of the Mediterranean entailed the presence of more or less permanently resident Venetian merchants in the Levantine marketplaces from the 13th Century onwards. The Palestinian-Syrian coast , in particular, saw a good deal of colonisation by Venetian merchants, as the towns along this coast played a crucial role as the Mediterranean outlets for many goods from India and Persia.

In the case of Acre, Venetian merchants occupied an entire district of the city. There were also large communities in Beirut and Cyprus.

With the coming of the

Mameluks and later the

Ottomans in the 16th Century onwards, Aleppo monopolised trade in the goods brought by desert caravans from Basra and Baghdad .

As a result, European merchants wanting to do business in Syria had no alternative but to open offices in Aleppo: its famous covered market at the foot of the citadel expanded to become the biggest bazaar in the Levant.

The Venetian communities, referred to as Venediklü taifesi in Ottoman documents, were formed by individuals performing various different tasks within the same trading system.

More specifically, there were merchants who travelled to and from the Serenissima Dominante (i.e. Venice), stopping just long enough in the East to strike their deals. They were met in Aleppo, Istanbul or Alexandria by a Consul who changed every four or five years and a colony of resident merchants, often called "fattori" (agents).

Consuls were young mainly (but not exclusively) Italian men: their actual place of birth was of less importance than its falling under Venetian protection and significance in terms of trade with the Rialto market.

As a Venetian Ambassador in Istanbul (the bailo) complained in the mid 16th Century, these agents were often the cause of misunderstandings and disputes with the local administration, given that they were more likely to commit offences owing to their close contact with the rest of the population than any passing merchant.

A letter sent by the Ottoman Sultan Selim II to the Governor of Aleppo on the eve of the war in Cyprus (1570) gives a better idea of the size of the resident Venetian colony in that Syrian city: worried about the possibility that the military conflict might turn merchant networks into spy networks, the Sultan asked the Governor to control all movements of the Venetian subjects and “protégés”, at the same time seizing their tangible and intangible assets.

A detailed inventory of the latter was to be sent to Istanbul.

This request by the Emperor proves that the property in question was not limited to the lodging house (the khan ), the Turkish bath and the church of the Forty Martyrs, but far greater properties, which were handed back three years later at the end of the war.

The khan was a Mediaeval building quite distinct from the consulate and was located inside the market for passing merchants and their merchandise.

A circular building around a courtyard, its huge gate leading to the market was closed every night.

The most important interruption in the long life of the Venetian colony in Aleppo occurred during the War of Candia (1645-1669), when the consulate was abolished and the Church of the Forty Martyrs (where many Venetians were buried) was confiscated and transferred to the powerful local Armenian community.

The consulate archives (which probably contained documents dating back to the previous century) were sealed by the last Consul and handed to a merchant for safe transport back to Venice: the merchant lost these, together with his life, in the desert outside the city under very suspicious circumstances.

The consulate was reopened in the 1740s, but by this time trade and the merchants of Aleppo had irreversibly changed, being dominated by the economic activity of the Chambre de Commerce de Marseille. The consulate building is still owned by the descendants of the family of the last Venetian Consul, who, like many others, decided to stay in Syria under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, even after the fall of the Republic.

Inside, you can still see the banner of the lion of St. Mark, carpets, furniture and paintings depicting a mixed society that has now disappeared: the Consul’s wife, dressed in European style and sipping a Turkish coffee, assisted by a maid in Turkish clothing with gold flowers embroidered on silk fabric.

Vera Costantini