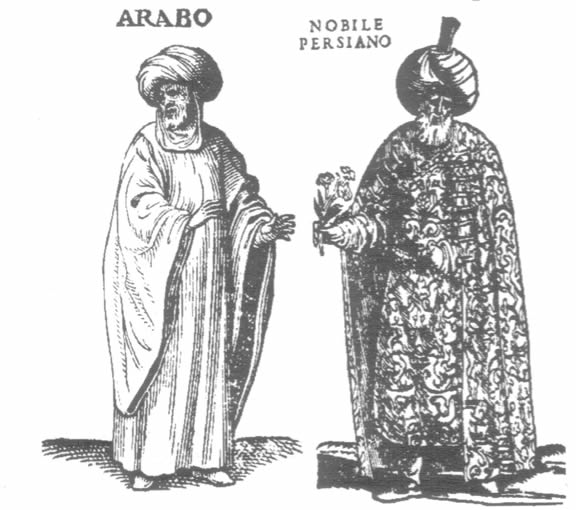

A cosmopolitan, multiethnic city from the very outset, Venice has always allowed people coming from different countries and of different religions to live together in a climate mutual tolerance, seeing them as a source of enrichment for its economic, political and cultural heritage.

These "foresti" , as all those who went to Venice for short periods or to live there permanently were called, were accepted irrespective of their social class or religious beliefs and took an active part in the life of the city at various levels.

The reciprocal influences of different cultures in Venice can be seen in many areas and components of life in Venice.

Here are just a few of the more curious:

Venetian traditions

The official birthday of Venice is March 25th, 421. The choice of this day, decided upon round about the year one thousand, was by no means random, but has a philosophical and symbolic value. The ancient chronicles remind us that on this day the first stone of the church of San Giacometto in Rialto was laid, mistakenly thought to be the oldest in Venice. This date - completely legendary - was immediately held dear by the religious Venetians because it coincided with the day devoted to the Annunciation and, according to a Greek belief, with the creation of the world.

Venetian art

The plaque of Santa Maria in Torcello

The plaque commemorating the foundation of the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Torcello in 639 AC clearly indicates that it was due to the will of the Armenian Exarch Isacio: “Imperante Eraclio Augusto e per ordine di Isacio esarca e patrizio” ("Emperore Heraclius Augustus and by order of Isacio Exarch and patrician") .

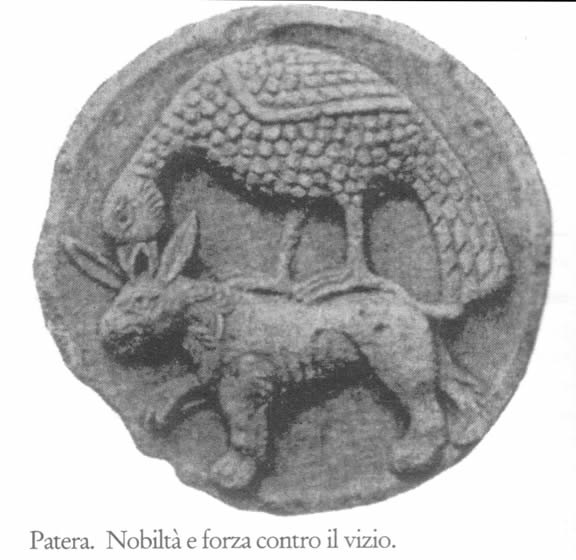

Patere

“Patere” - from the Greek "πατερα" for the round bowl used for sacrifices and libations - were sometimes finely worked in bas-relief or decorated. The use of patere spread throughout Italy between the 2nd and 5th Centuries and continued to be used in Venice until the 14th and 15th Centuries and even later.These “external sculptures” are relatively easy to catalogue and place. Some of them represent the places of origin or the type of trade plied by the purchaser.

The interpretation of the Venetian-Byzantine patere is much more complicated, with their depictions of animals or fantastic anthropomorphic figures.

The one in the wall of Palazzo Gritti Badoer , above the Gothic window with five lights on the first floor, depicts a peacock with its tail fully extended. The peacock had a special meaning: the incorruptibility of flesh. That is why the peacock became the symbol of immortality and resurrection in Byzantine art. Patere representing fighting animals are usually symbolic references to the eternal struggle between good and evil. Animals drinking symbolise the thirst for knowledge; those eating grapes, abundance and goodness; those embracing , love and harmony.

Graffiti

Graffiti in Venice can be found virtually everywhere. Unfortunately, most are no longer legible in Venice today, such as the two runes on the sides of the lion placed on the left side of the portal of the Arsenale, which was taken from the port of Athens along with the lioness and two cubs by Admiral Francesco Morosini in 1687. Just 20 years ago the graffiti could still be read with a sliding light.

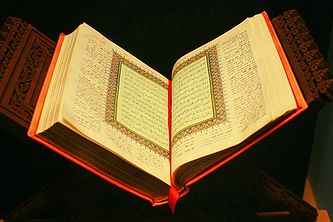

St. Peter’s Throne

In the right nave of San Pietro di Castello - the Cathedral of Venice until 1807 - is the famous "St. Peter’s Throne" attributed to St. Peter of Antioch (11th-12th Century). Tradition has it that it was donated by Michael III Paleologus, Emperor of the East (842-867). The back is formed by a stele inscribed with decorative Arabs motifs and verses from the Koran.

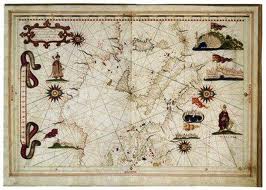

Navigation

The Astrolabe and Portolano

Crucial instruments for navigation introduced by the Arabs, these were used daily by Venetian sailors. The astrolabe showed the heavenly vault; the portolano the major Mediterranean ports in the 15th Century.

Printing

The Canon of Avicenna

The translation of the Handbook of Medicine by the Persian scientist Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980-1037) was published in Venice and adopted by the University of Padua.

The Cabala

The study of the Cabala, sometimes accompanied by magical interpretations, was introduced when Venice opened its gates to the Jews fleeing from Spain (Sefardics). Cabalistic studies became especially important in Padua. A Christian interpretation of the Cabala was created in Padua, thanks mainly to the work of Pico della Mirandola. Tiny underground communities sprang up towards the end of the 1500 and early 1600s: the initiation sects of Rosa-Croce and Freemasonry. The latter still exists today, although not always with the original intentions of its founders. Lucky amulets are the best documented "magical" aspects can be found in the Jewish Sefardic culture.

The Koran

The oldest and perhaps the first printed edition of the Koran was produced in Venice, in Arabic.

Venetian cuisine

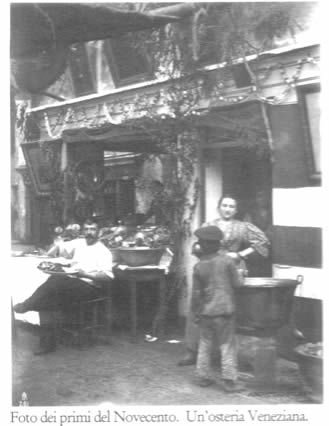

Even Venice’s culinary art proves the openness and willingness of this city to welcome other people and their culture, plus the Venetians’ pragmatism. "If he, the ‘foresto’, can eat it, then I can try it too."

Stable communities from all over the world lived in Venice. It is no coincidence, therefore, that many of the recipes for popular dishes in Venice are also compatible with Jewish and Muslim dietary rules on account of their ingredients. Even the slaughter of animals often involved the practice of cutting the animal’s throat and leaving it to bleed dry. Owing to the Jewish and Islamic practice not to eat pork, it seems very likely that Venice introduced duck and turkey to replace pork sausages and even ham.

The “luganeghe”, the famous sausages often combined with risotto, could be made using beef, not pork. Dry salted cod “baccalà” seems to have been imported from the North Sea by a noble Venetian, Piero Querini, who happened to land on the Lofoten islands. This has become one of Venice’s most typical and tasty dishes: "baccalà mantecato" (creamed cod).Spices and sweet’n’sour recipes are often used for fish dishes, such as the famous "sarde in saor" spiced sardines used by sailors on account of their long shelf-life and high vitamin content, thus a good precaution against scurvy.

The language

Many Venetian terms are clearly of foreign origin. The fruit of the peach tree (Amygdalus Persica) is called “pèrsego” in Venetian, indicating the place of origin: Persia. The fruit of the apricot tree (Armenius Armenia) is called “armelìn”. Many terms are of Arab origin, such as “fondaco” (goods warehouse) from funduq; “darsena” (small harbour) from "dar as – sine" and “zecca” (where coins are minted) from "dặr as – sikka". Likewise, “Arsenale” is an Arab term meaning a place for the building, repair and upkeep of ships, comes from "dar as-sin’ah", while the greeting, “ciao”, was originally a Venetian expression, now used worldwide.

Everyday life

As in other Mediterranean countries, many activities were carried out in the open air probably for practical reasons: better light, quickly dispersed smells, more socialising, the chance to "Ciacolar" and share in other people’s lives. Not only would the fishmongers "tagiar tabarri", but also the pearl threaders as they threaded their necklaces, the baccalà beaters , the inn-keepers and the fortune-readers .

Contacts with the Far East

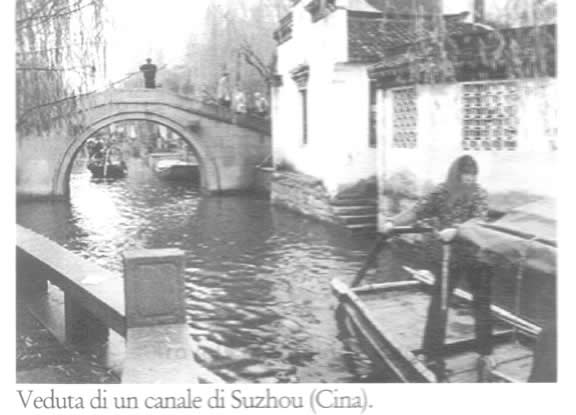

More and more people are becoming interested in oriental studies, but we still have only partial information on the mutual influence resulting from trade between Venice and the province of Catai in China over the centuries. Of course, the milestone in the history of these voyages is the book Il Milione by Marco Polo. It is hard to believe, however, that after so many trips and long stays in the East, the Venetians just adopted the use of spices: what about the scientific knowledge and technologies in the Far East, such as paper, gun-powder, spaghetti, the compass, etc. For what we know, however, nobody has ever paused to reflect on certain coincidences. For instance, the Venetian style of rowing is for the rower to push the boat along with a single oar with an elongated teardrop profile resting on a "Forcola", he stands as he rows and the boats have a flat bottom: just like the "sandal" used by the Chinese in their numerous lagoons .

Only two types of arch were known in Europe until the early 14th Century: the fully rounded arch and the sharper Gothic arch. As the plan of the city drawn by Jacopo Barbari (1500) shows, most of the bridges in Venice at the time were still built from wood. These consisted of flat planks called "toletta" that also let those on horseback cross the canals as they had no steps. The only exception was the Rialto bridge, with its horizontal plan, as can be clearly seen on the telèro by Vittore Carpaccio “Il Miracolo della Croce”. The extreme elegance and lightness typical of Chinese bridges is found in the bridges in Venice if we strip them of their steps and abutments, i.e. their original design. It is likely that Marco Polo, on his return to the city, brought with him some Chinese “Protos” or, more simply, drawings and construction techniques from the East.

Personal appearance

The use of precious fabrics, ornaments, earrings, fragrances, personal hygiene and perhaps even the desire to change hair colour adopted by the Venetian women is typically Oriental. The famous Venetian red hair was obtained through exposing only hair treated with a lightening acid to the sun. The face, on the other hand, was protected from the sun with the help of a large flap that was part of the equipment used and called a “solana”.

Franco Filippi