Lagoon of Venice. Satellite images of the lagoon (May 2005). In the centre, the city of Venice. Along the coast, thin strips of land separate the lagoon from the sea. Three apertures can be seen: the port entrances, through which the tides of the Adriatic flow into the lagoon.

Venice. Birds-eye view of the city. In the centre, St. Mark's Square.

The island of Torcello. In addition to the historical island-cities of the lagoon, such as Venice and Chioggia, l Chioggia, the lagoon is dotted with numerous

Mudflats and sandbars. The mudflats, known locally as �velme�, are normally submerged areas of the lagoon, which only appear during low tides, while the sandbars are firm stretches of sand that almost always emerge above the level of the waters and are only occasionally submerged. The sandbars are an irreplaceable habitat for the flora, fauna and bird-life of the lagoon and have various important functions: they regulate the hydrodynamics and cushion the motion of the waves.

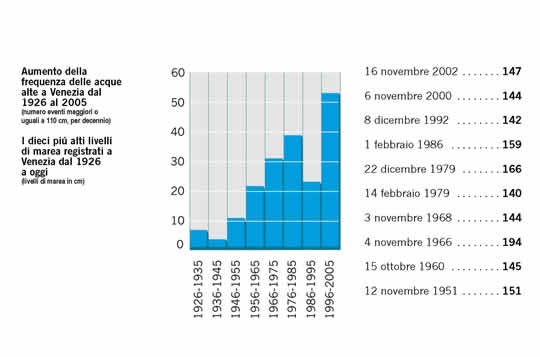

November 4th, 1966, St. Mark's Square. The water level rose to + 194 cm and Venice, all the islands in the lagoon and the lagoon itself were submerged by over a metre of water.

The increase in the frequency of acqua alta in Venice. The data.

Acqua alta in Venice. Flooding creates problems for residents and damages architectural structures and buildings. The higher the tide, the wider the area affected and the worse the damage.

Acqua alta in Venice. Flooding creates problems for residents and damages architectural structures and buildings. The higher the tide, the wider the area affected and the worse the damage.

Acqua alta in Venice. Flooding creates problems for residents and damages architectural structures and buildings. The higher the tide, the wider the area affected and the worse the damage.

Acqua alta in Venice. Flooding creates problems for residents and damages architectural structures and buildings. The higher the tide, the wider the area affected and the worse the damage.

Lagoon of Venice. Locations of the port entrances

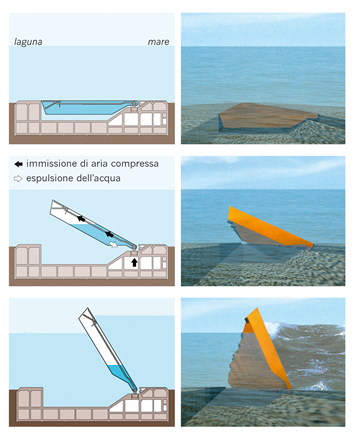

MOSE System. How the barrier moves. The MOSE System consists of a series of sluice gates that lie under the water during normal tide conditions, i.e. completely invisible, and are hinged to bases on the seabed in the three port entrances. However, if a high tide is foreseen, compressed air empties the gates of water letting them rise to the surface, thus creating a continuous barrier between the sea and the lagoon for as long as is required.

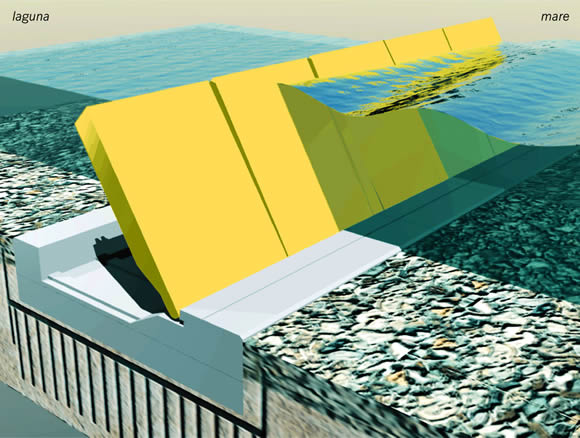

MOSE System. Detail of a barrier in operation. When the MOSE System is in operation, it creates a continuous barrier between the sea and the lagoon for as long as is required, but without interfering with port activities, as it provides safe harbours and locks to allow vessels to enter when the barriers are raised: locks for pleasure craft and fishing vessels heading for Lido and Chioggia, plus a large lock for ships heading for the port of Malamocco.

MOSE System. Construction at the Lido port entrance (October 2007). In the centre, the new island between the two series of sluice gates planned for this entrance. In the foreground, the reinforced pier and the shoulder of one of the barriers. Behind the new island, part of the safe harbour and the inlet leading to the lagoon for small boats when the barrier is raised.

MOSE System. Construction at the Lido port entrance (October 2007). In the centre, the safe harbour with the inlet for entry into the lagoon by small boats when the barrier is raised. The seawards part of the safe harbour has been planned to act as a temporary area for precasting the barrier foundations. On the right, the new island between the two series of sluice gates planned for this entrance.

MOSE System. Construction at the Malamocco port entrance (October 2007). In the foreground, the new completed barrier. Behind the barrier, the inlet allowing large vessels to pass through when the barrier is raised. On the left, the temporary area used for precasting the barrier foundations. In the background on the left, the new Pellestrina beach, where the shoreline has been strengthened to create a continuous sea defence together with the port entrance.

MOSE System. Construction at the Chioggia port entrance (October 2007). The two inlets for fishing vessels when the barrier is raised and the �shoulders�. In the background, the old town of Chioggia.

The Pellestrina coastline before and after the creation of the new beach. The entire Venetian coastline has been boosted and protected and, where possible, the dunes have been reintroduced.

The Pellestrina coastline before and after the creation of the new beach. The entire Venetian coastline has been boosted and protected and, where possible, the dunes have been reintroduced.

The Pellestrina coastline. View of the new beach that protects the coast against sea storms.

An eroding sandbar. Signs of erosion along the edge of the sandbar caused by tides and waves, wind and shipping.

Protection of a seriously eroded sandbar. Sandbars are crucial parts of the lagoon environment: they provide an irreplaceable habitat for the flora, fauna and bird-life of the lagoon, regulate the hydrodynamics and cushion the motion of the waves. Erosion processes could well lead to their disappearance, hence the need to protect them.

Protection of a seriously eroded sandbar. Sandbars are crucial parts of the lagoon environment: they provide an irreplaceable habitat for the flora, fauna and bird-life of the lagoon, regulate the hydrodynamics and cushion the motion of the waves. Erosion processes could well lead to their disappearance, hence the need to protect them.

A sandbar in the process of construction. Sandbars are reconstructed by pouring the sediment dredged from the lagoon inlets into an area with a continuous �fence� around it. The surface of the sandbar is then colonised by typical plants, often especially planted for that purpose.

Re-vegetation of a reconstructed sandbar. A recently finished new sandbar, showing how �pioneer� plants gradually take hold (especially the saltwort), until it is completely colonised by plants.

Porto Marghera. Southern industrial canal. The banks before and after work to make them environmentally safe, thus preventing the release of old pollutants in the soil through the banks of the industrial canals.

Porto Marghera. Southern industrial canal. Detail of the works.

Island of Cerosa. The banks of the island are exposed to erosion and degradation: before and after reclaiming.

Island of Cerosa. The banks of the island are exposed to erosion and degradation: before and after reclaiming.