Venice was the undisputed centre of the Adriatic and Mediterranean markets during the Middle-Ages. The movement of people, goods and ideas - from East to West, from the Alps to the coast of Africa - gave the port that developed around the island of Rialto an exceptional role: it became the biggest melting-pot of peoples and cultures in the Mediterranean.

Venice is by no means an ancient city - i.e. a Roman city - like so many other cities on the Italian peninsula, but is an extraordinary "product" of an early Mediterranean and European culture.

In recent years numerous archaeological excavations have allowed us to discover the early stages of the city, resulting in new interpretations of the extraordinary and fascinating problem of the true origins of the city.

Venice before Venice

Thanks to archaeological research into the post-classical phases of Venice and its area we now have a better understanding of the material characteristics of the first settlements on the islands in the lagoon.

Venice, as we know it today, was founded in the early 9th Century.

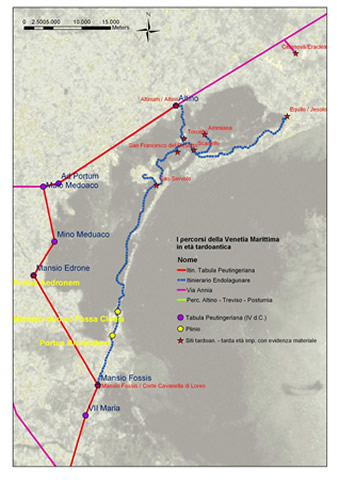

Before this, during Late Antiquity, there were various small settlements on the barene in the lagoon. The “industries” were mainly linked to the exploitation of the resources of the lagoon (salt and fishing) and the land edging the salty water.

The archaeological sequences found during the excavations of San Francesco del Deserto and Torcello show that the lagoon became intensely populated in the 5th and 6th Centuries.

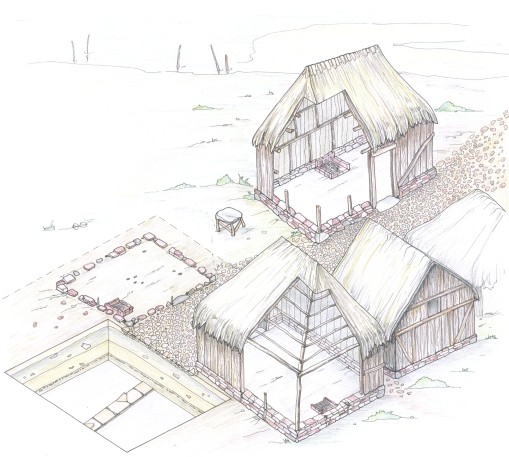

Despite worsening accessibility to the islands owing to an increase in the average sea level - as proven by large sections of mollusc-rich alluvial saltwater deposits (bittium) - excavations have brought to light dwellings made almost exclusively in wood, defended against attack by invaders and the sea by banks and waterfronts. Again, there are clear traces of wooden dwellings with recycled brick and beam foundations in San Pietro in Castello (the Episcopal See in 775-76) and in the garden of what is today the Casinò Municipale: the materials were taken from older Roman buildings around the lagoon.

The type of "material culture" (artefacts and structures) coming from these sites lead us to assume that the settlements continued to be open to the Mediterranean markets and capable of certifying imported pottery (amphorae and crockery) from the 4th to the 8th Centuries. In all likelihood, the economy of these communities was strongly supported by the local fishermen and sailors, guaranteeing transport of goods and products within the lagoon, from Ravenna (the imperial court) to the North (Aquileia and Istria).

These lagoon communities were governed by “tribuni maritimorum” (courts of the sea) and so prove there was considerable trading going on. The settlements invested considerable amounts in earthworks and defences to protect the land (thanks also to the profits made from the sale of salt), way before the transfer of administrative and religious power to Torcello and Olivolo.

The birth of the city: the archaeology of a legend

The birth of Venice is a legend. It has often been claimed that Venice developed as a result of "devastating" incursions by the "barbarians", adding detail to the legendary ferocity of Attila the Hun and the Germanic Lombards. According to this legend – encouraged as propaganda by the Venetian Registry during the central

Middle-Ages – Venice was founded by refugees fleeing from besieged Roman cities inland. These

Byzantine exiles found refuge on the safer lagoon islands and so are responsible for building the city we know today.

Archaeological surveys, however, tell a different story. A more complex and definitely more fascinating story.

The layers of subsoil in the lagoon and in the remains of Roman cities inland do not, as one would expect, point to a sudden moment in time, but gradual development of the settlements on the lagoon. Of course, the new political status-quo in Venetia (consolidated in the 7th Century with the formation of the Lombard kingdom in the Po Valley and the stabilisation of Byzantine influence along the coasts) stimulated and finalised the transfer of administrative, cultural and economic powers to the main island of Rialto.

Pottery, wooden artefacts, coins, the shape of these settlements and their commercial infrastructure tell us how the harbour functions typical of the Roman cities inland were transferred to these islands surrounded by salt water.

The ports and entrance canals became silted up at the end of the Imperial Age, yet contacts with the East continued, albeit in different forms. Torcello and Cittanova inherited the functions of the emporium (centre of commerce) from Altino and Oderzo respectively.

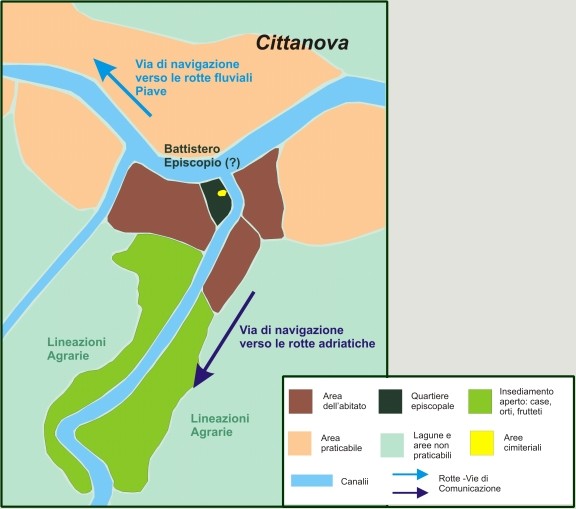

The first Venetian Dux was formally elected in Cittanova. Archaeological studies have shown how parts of the Episcopal See were integrated to form a complex structure in the lagoon area. A dense network of canals and drains built in the 4th Century ad and clearly visible in aerial photographs show how large sections of the lagoon either side of a navigable canal had been reclaimed.

Houses with wooden landing stages and docks lined the canal in the early Middle-Ages. The "fortune" of these inhabitants was due to the income they enjoyed from substantial their farmlands. The material culture, however, shows that strong trading was already taking place around the Adriatic and the Mediterranean.

Torcello, the seat of ecclesiastical power in the 7th Century

It is believed that the Episcopal See was moved from Altino to Torcello in the 7th Century. A much debated inscription dated 639 mentions a "Magister militum” on whose land the church would be built.

Excavations at the Basilica di Santa Maria Assunta, however, suggest that construction took place at end the 7th Century / early 8th Century under the aegis of Deusdedit I. What really matters, however, is the huge financial investment involved, a sort of surplus coming from the merchants used for the construction and decoration of this religious building. Excavations have revealed the complex sequence in the area of the baptistery and fourth nave .

Archaeological discoveries confirm that there was rich stable community here, proven also by the presence of metal and glass workshops.

Constantino Porfirogenito in the 10th Century defined Torcello as an Emporion Mega (major centre of commerce).

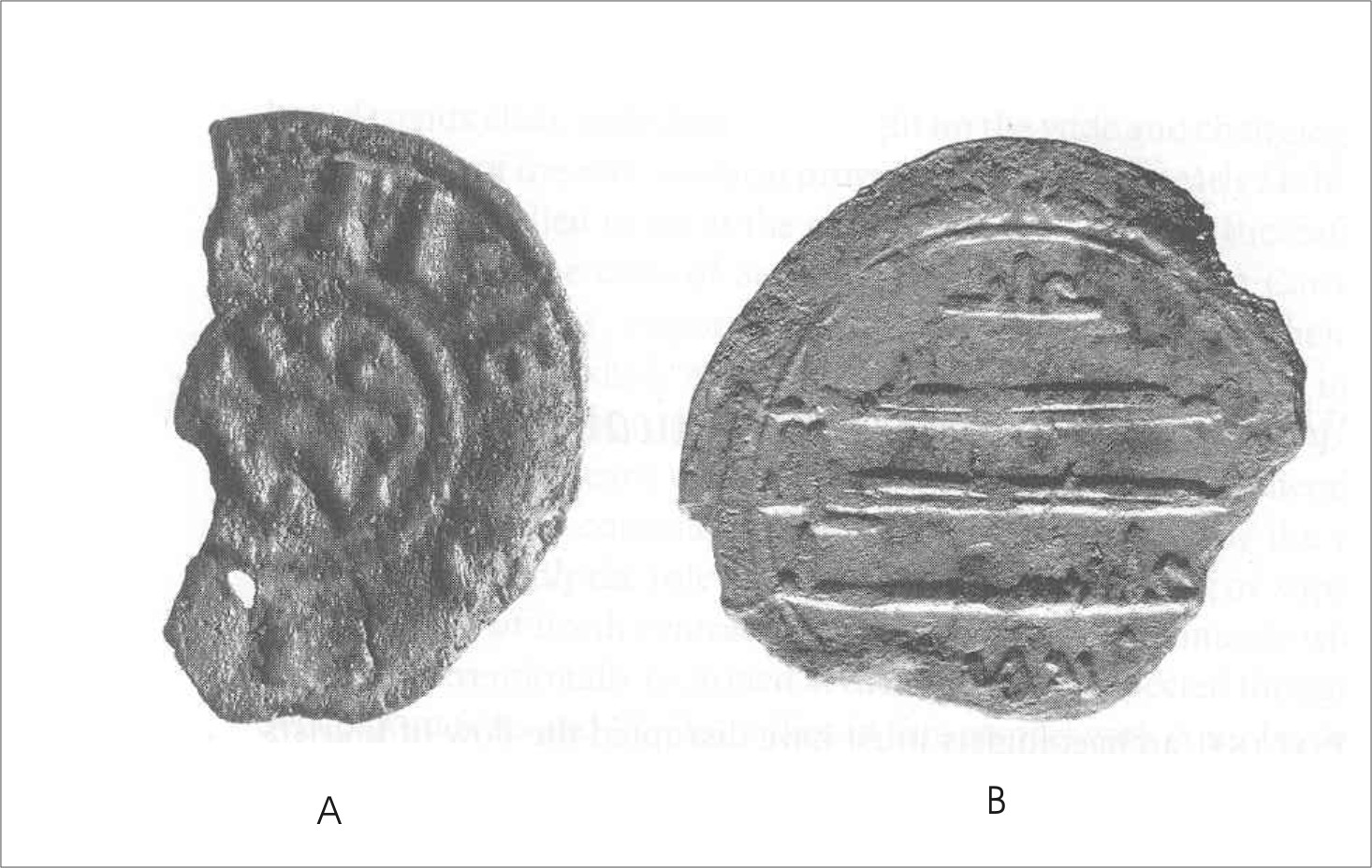

The economic vitality of the island is best proved by a coin of Charlemagne found together with an Arab dirham dated the 2nd Century of the Hejira .

The lagoons around Venice had thus become places of intense and continuous trading - not only of goods but also of ideas – with both areas of the East, Arab (Alexandria) and Byzantine (Constantinople).

Venice, the Adriatic emporium of Mediterranean Europe. Venice between the Byzantine and Carolingian eras

Archaeological excavations and analysis of pottery show how the Venetians quickly penetrated the Adriatic and Mediterranean markets and were favoured business partners for the inland Po Valley kingdoms.

Trade, yes. But what was the merchandise? Virtually anything, from sacred relics to slaves, from spices to textiles, from oil and wine to timber, stones and weapons... Eastern products required in the West, Western products with markets in the East.

An increasingly complex network of deals, a game of supply and demand that first meant Byzantine ships sailed up into the Adriatic and later saw the monopoly of Venice when it came to commercial shipping. Not to mention the important salt market.

Trade, yes. But for whom?

Unlike the inland towns, the early lagoon settlements managed to keep contact with the Byzantine Empire. In fact, they were nominally Byzantine for a long time to come, and therefore belong to an area where specific goods (Oriental products) were demanded and shipped.

These goods gradually attracted the interest of the Lombard and Frankish elite.

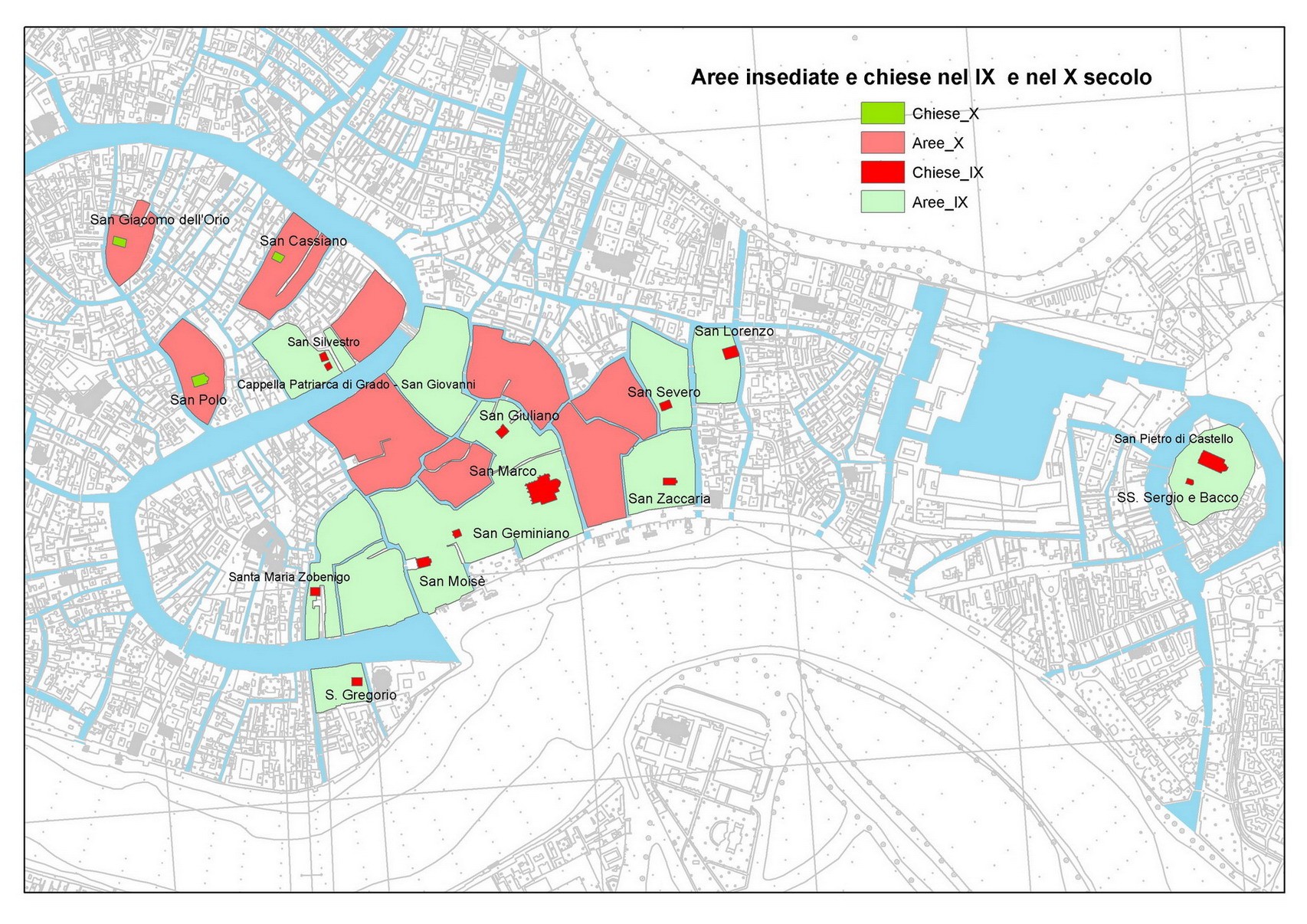

Venice in the 9th and 10th Centuries consolidated its role as a major centre of commerce across the Mediterranean and Europe.

This was partly due to the stability of aristocratic hegemonic Carolingian world and thus the “demand” factor of economics in the early Middle-Ages. Valuable goods passed through Venice on their way to and from complex areas (the Byzantine and Frankish worlds). Yet Venice was also a place of regular local trade with neighbouring areas on the mainland: a role probably inherited from the immediately preceding period.

Archaeology and Venice. Evaluation of the archaeological resources in the lagoon

Researchers at the School of Medieval Archaeology (Department of Antiquity and Near East Studies at the Ca’ Foscari

Researchers at the School of Medieval Archaeology (Department of Antiquity and Near East Studies at the Ca’ Foscari University, Venice) have set themselves the goal of reconstructing the archaeological history of Venice by means of a systematic review of all existing excavation data (Italian state-led excavations, research by the School of Poland, studies by other Italian and foreign researchers).

All data have been collected using a GIS analysis tool (Geographic Information System Place) and then linked to the data from new sites: the aim is to rebuild the complex archaeological history of Venice.

This study aims to provide advanced tools for reading archaeological documents and provide strong guidelines for assessing the quality and quantity of archaeological resources in the Venice area. Not a simple map of excavated sites, but a means for learning, assessing and deciding .

Its purpose is to turn archaeological research from a fragmented activity with an "antique" feel to it into a proper science with the awareness that “mature” archaeology is an independent means of understanding people, cultures and events.

Archaeological resources in Venice are of inestimable value. Not just the subsoil, but also the verticality of the city: from the bottom of the canals to the top of its palaces, Venice is an exceptional document of history and culture.

Venetian archaeological studies, therefore, need to be planned and suitable for the assigned task. A specific project is always needed – research, analysis, excavation, restoration and documentation – so that the basic principles of preservation, knowledge and understanding are guaranteed. These principles are set out in a code of ethics for the restoration of the city, deliberately called the "Charter of Venice", edited by ICOMOS (website at www.ICOMOS.org).

Diego Calaon