In the 18th Century Venice became known as "the city of Masks": people would wear masks for six months, the duration of Carnevale. The city became transformed: the magnificence of its decadence had no equal . Venice welcomed people coming from the West and the East, noble intellectuals and adventurers , who invaded the campi, campielli, calli and especially St. Mark’s Square.

Fifteen theatres opened their doors in Venice during the Carnival period. A group of Signori controlled the fate of the Serenissima, while Barnabotti, argued about their lost privileges and allowed themselves to be manoeuvred in exchange for favours.

This was the setting for the Venetian festivities that Watteau has immortalised in his paintings. Gabriele Bella portrays moments of real Venetian life in his naive paintings.

The "festa della Sensa" , the feast of Ascension Day, saw the Bucintoro (large golden galley) dominating a host of boats and gondolas, as part of the sea celebrations of the ceremony of the "Sposalizio col Mare" (Wedding of the Sea).

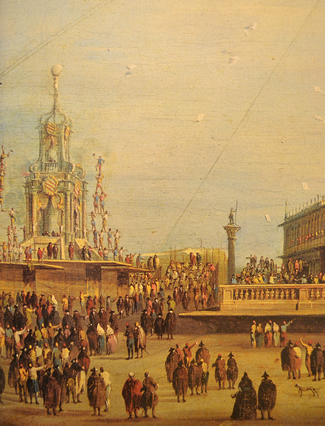

Meanwhile, there was a fair in St. Mark’s Square in the wooden semicircle, last erected in 1777 by the architect Maccaruzzi.

The height of Carnevale was the feast of Giovedì grasso.

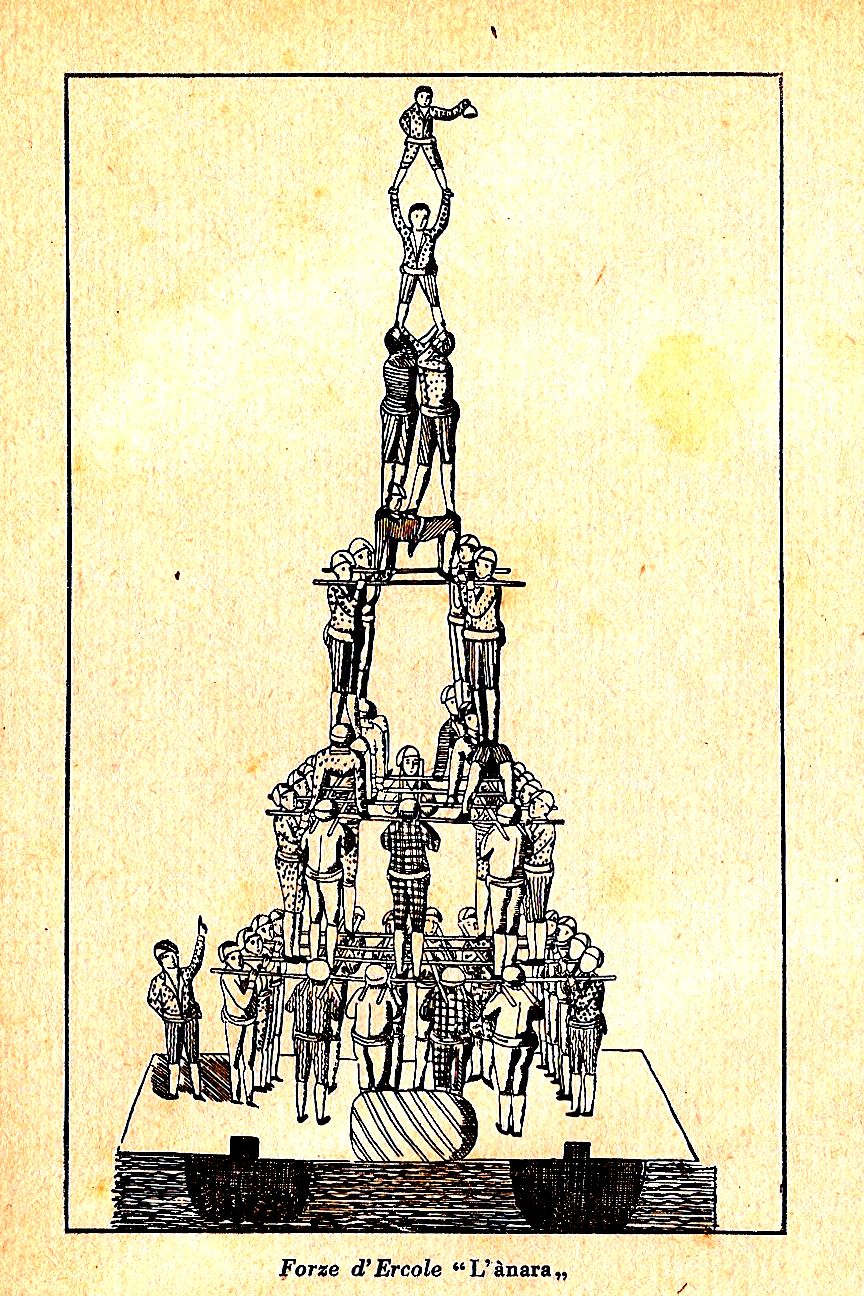

The great "Macchina" was set up in St. Mark’s Square, housing the orchestra. Fireworks shot out from the "Macchina" to end the show. The "colombina" flew down from the bell-tower of St. Mark’s Basilica along a rope leading to the Loggia Foscara in the Doge’s Palace where the Doge stood, ready to receive flowers and poems. Forze d'Ercole” acrobats performed against a cheerful background of pipes, trumpets and drums: human pyramids by the Nicolotti and Castellani, competing Venetian factions that fought fierce battles until the early 1700s on the Santa Fosca and Canale Santa Barnaba, armed with rods and fists.

In the 18th Century, the tents hosting charlatans , astrologists, tooth drawers, magicians, puppet theatres, singers, fortune readers, touts and improvisers were very popular during Carnevale. The most successful were the lion show , the Irish giant Magrat and the rhinoceros , immortalized by Pietro Longhi in his small masterpieces.

The "Mondo Nuovo" (New World) was another popular event, featured in one of Giandomenico Tiepolo’s masterpieces.

The coronation of the Doge, after his election, on the Scale dei Giganti in the Doge’s Palace was a particularly theatrical moment and the height of the ceremonies for the Venetian nobility.

After reading the “Promisione” and the oath to observe this, the youngest member of the Council put the "Camauro di Rensa" on the Doge’s head and then the oldest member placed the "Zogia" (Doge’s Horn) on top of this amidst the applause and shouts of encouragement from the public.

On the day of San Rocco , the Doge was accompanied by the procuratori and senators of the Republic on a visit to the Church of San Rocco and "Scuola di San Rocco" where the annual painters’ fair was held.

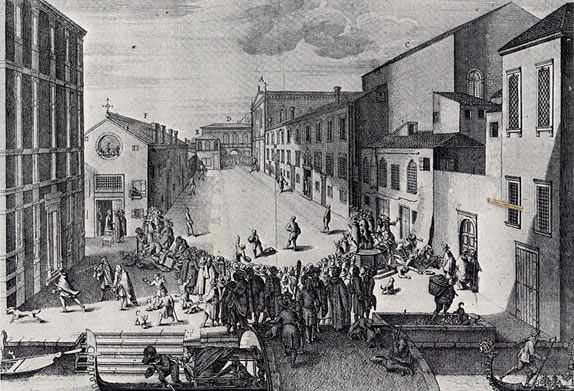

A fine Canaletto's painting shows us the Doge between two crowds of people in Campo San Rocco, standing under a large tent specially set up for the occasion.

There was a vast choice of entertainment in Venice. Gambling dominated everything, continuing all day and all night.

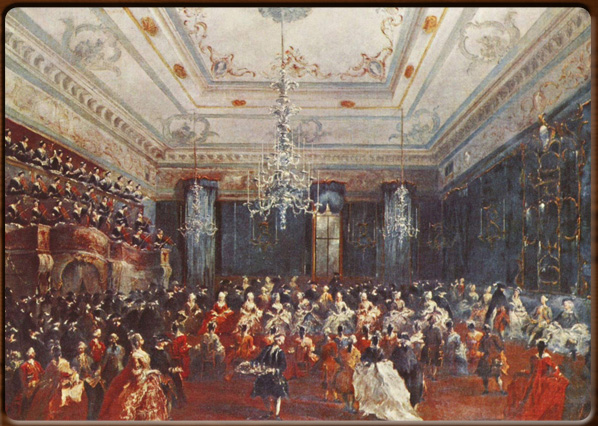

In the end, the Greater Council was forced to ban gambling, describing it as "solemn, continuous, universal and violent". In the 1700s the Ridotto di Ca' Dandolo symbolised the magnificence, elegance and fame of Venice and Bella regularly painted it . This temple of fortune in a city that worshipped gold teems with masked ladies and gentlemen, while a few women in local costume accompany and serve their mistresses.

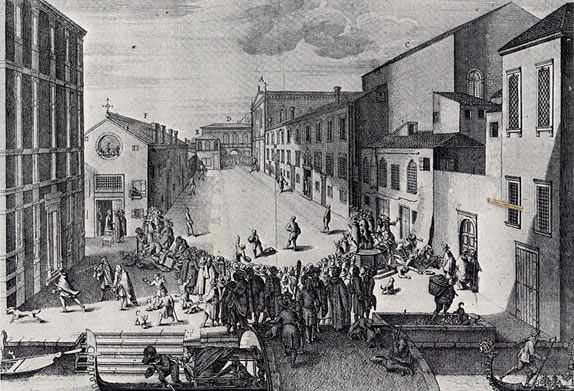

Balls and dances would be organised in the campi and campielli during Carnevale. The people were only too happy to have fun, accompanied by even just a few musical instruments.

The long period of penance and Lent was interrupted by a popular festival called the "Segavecchia", again portrayed by Bella. On a stage erected in the centre of a square, a puppet is dressed in popular Venetian costume. This puppet represents an old decrepit woman (Lent), to be tried and sentenced. At the end of the trial the puppet is convicted and sawn in half, amidst a great uproar and the sounds of pipes, trumpets and drums. Sweets and fruit fall from the puppet onto the public below.

A particularly cruel festival is the "Cazza del Toro" (Bull Hunt), a kind of bullfight with dogs which used to be held in some areas of Venice, among which Campo San Geremia and Campo San Polo.

Anyone could have fun in Venice: the “Gioco del Pallone” (ball-game) only required four players and could be played in any public place. Occasionally someone in the public or an unsuspecting passer would be killed by a flying ball. People would bet on the outcome of the matches. There was great shouting, screaming and blasphemous or vulgar joking that forced the Esecutori alla Bestemmia (Protectors of Public Morals) to repeatedly ban the game.

Fantastic events were also held by the Serenissima for the Grand Duke and heir to the throne of Russia, Paul Petrowitz – son of Peter III and Catherine the Great and later to become Tsar Paul I – and his wife when they visited Venice in January 1782.

After a few years the Republic of St. Mark would disappear.

Michelangelo Mandich