By the beginning of the 19th Century Venice was no longer a capital city.

It had long lost its economic status and its political power was gradually diminishing. After the fall of the Republic, Venice simply became just one of the many pieces in the big jigsaw puzzle of major European alliances.

Napoleonic occupation was brief but eventful, leaving Venice with a far-sighted plan for its modernisation.

Although never completed, the idea fuelled the city’s future development: the possibility of a link with the mainland, the re-launch of the port within Europe, a network of large urban facilities, impressive public gardens and re-qualification of the city centre.

All supported by sound administrative initiatives, involving typical Napoleonic re-organisation into Departments (Venice would become the capital of the Adriatic department), modern public administration, a proper catasto, confiscation of Church property and restructuring of many buildings to accommodate the new urban facilities. A few initial steps were actually taken: Via Eugenia in Castello (now Via Garibaldi), which would be the beginning of the link with the mainland, the public gardens still in Castello and San Marco instead of the old granary and the rebuilding of the lagoon defences near St. Mark’s Square (and at the same time the demolition of many buildings, especially religious ones, and the massive plundering of churches and Scuole, i.e. the "lost Venice" of which only a fraction was later recovered).

Austrian occupation meant these far-reaching innovations came to a halt, as power and importance was shifted to another area: Trieste, where the port was in the process of being launched.

However, although these were years of serious economic decline and a truly dramatic demographic crisis, it was the port that finally changed Venice’s fate (in 1830 the whole city became a tax-free area, “Porto franco”, a status previously limited to the island of San Giorgio in 1806).

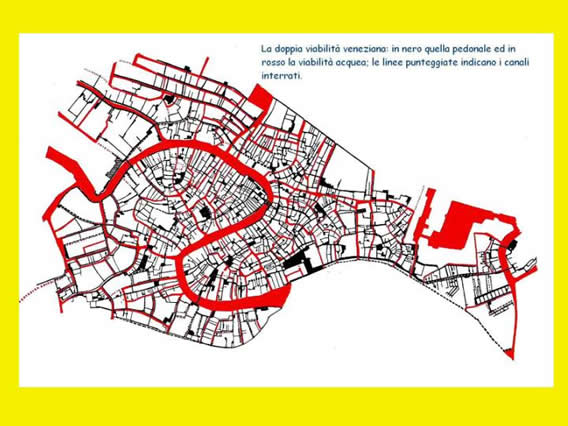

This economic recovery was also guaranteed by the Milan/Venice railway (1846), together with the construction of the first iron bridge over Canal Grande opposite the railway station (1858), four years after that of the Accademia bridge (1854). Moreover, many of the smaller canals were filled in and new pedestrian ways were created, especially on the edges of the city.

More and more works were planned for Venice and actually completed, despite the political changes after the Unification of Italy: the railway station was officially opened in 1865 and Strada Nuova was built immediately afterwards (between 1867 and 1871): this would become the major route from the station to the centre. In 1880 it was the turn of the Stazione Maritimma terminal, confirming the port’s new role and consolidating the new port facing the mainland. The city apparently wanted to re-organise itself by focusing on three specific projects: the creation of a modern industrial zone linked to the port, re-planning of the centre and the launch of tourism (Venice and along the coast).

Industry started to appear along the edge of lagoon, thanks to foreign capital and attracted by the railway and port infrastructure and the presence of vast open areas (or land easily obtainable by reclaiming sacche and barene).

An early industrial scenario where being an island city was yet to become a negative factor. A large cluster of yards, sheds, warehouses, factories, railway lines, docks and cranes, typical of any modern city’s outskirts, soon spread along the western edge of the city. The huge Mulini Stuky mills were built in several stages on the island of Giudecca at the end of the 19th Century, now an eloquent symbol of this important period of the city’s development. Other factories soon followed, while along the south coast of the lagoon several shipyards were constructed for ships requiring repairs or laying-up, thus becoming part of the landscape of the island.

Later still, other working-class neighbourhoods developed in amongst the remains of the rich Renaissance gardens.

Consequently, housing was soon provided for factory workers in Celestia, San Giobbe and Santa Marta, while new middle-class areas sprang up in Sant’Elena and San Rocco, and more recently in Sacca Fisola.

Venice became one of the Italy’s leading industrial cities. Signs of the city’s industrial revolution are easier to see in Venice than in many other cities, as the factories have not been re-absorbed by more recent expansion of the city outskirts owing to the natural barrier of the lagoon, even if many such sites are now abandoned.

The centre was also modernised in the late 19th Century. A new pedestrian system connected to large water basins replaced the old routes between Rialto and San Marco, now lined with banks, offices and hotels.

Calle XXII Marzo (1880-1882) streamlined the route between Campo San Bartolomeo and Campo Manin. The Bacino Orseolo was re-organised. Plus wider streets, demolition and filling-up of canals, a bourgeois 19th century “extension” of St. Mark's Square, deliberately designed to fit in with the façade of the Napoleonic Wing finished only a few decades earlier.Further away from the centre, large hotels were being built, first along Canal Grande and Riva degli Schiavoni and then at Lido. Tourism was launched and Venice soon gained international appeal thanks to the idea and success of the "International Art Exhibition" (the Venice Biennale) in the pavilions built in Castello from 1922 onwards.

The "mainland face" of Venice gradually increased in importance, boosted by works on the other side of the lagoon: the great industrial zone and urban district of Marghera emphasised the role of the mainland and demanded better connections with the island city, confirmed by the creation of "Grande Venezia" (Greater Venice) in 1922 which brought together Venice, Mestre and Marghera, the islands and the coastline (with the exception of Chioggia) and the smaller towns around Mestre into a single administrative area. The road bridge was built in 1930-33, thus physically connecting these areas.

However, changes to Piazzale Roma with the addition of the large public garage started the gradual shift in Venice’s gravity Westwards, which has proved to be an on-going process, despite the simultaneous opening of Rio Nuovo to avoid the large bend in the Canal Grande and so make it quicker for boats to arrive in the old centre in an attempt to recover its economic importance.

Franco Mancuso