Venice’s lagoon has an extremely interesting submerged and emerged archaeological heritage as a result of both its long history of human occupation and its unique environment.

Owing to eustatic and bradyseismic phenomena, many of the ancient settlements around the lagoon are now submerged.

Numerous archaeological discoveries in the Venice lagoon area were made by Ernesto Canal, a self-taught archaeologist. Over the course of thirty years he found and documented dozens of sites of archaeological interest from the Roman period to the last few centuries.

More recently, the Italian authority for archaeology set up a separate local office – NAUSICAA (Nucleo Archeologia Umida Subacquea Italia Centro Alto Adriatica) – which has made it possible to catalogue all of Canal’s findings and now co-ordinates daily control activities during public works. This new institution is thus responsible for safeguarding all archaeological sites and finds in the lagoon area. Most of the archaeological work systematically carried out in the lagoon is funded by the Magistrato alle Acque – which has jurisdiction over the lagoon waters – via its agency Consorzio Venezia Nuova.

There are at least four stages in protecting these sites. First, there is a study of the history and environmental history of the area where the work is to be performed. The second stage takes the form of underwater exploration, with visual inspection or, in the case of deep water, using steel probes. The third consists in providing assistance during earth movements, while the fourth and last stage is archaeological excavation (if required).

The archaeology techniques used in the lagoon are quite unique, unlike those in other environments. The presence of water calls for underwater archaeologists and divers capable of working in conditions of low visibility (less than a metre) and often in strong currents. As a result, special recording techniques (including photographs) suitable for murky waters are adopted. Whenever possible, solid metal barriers are placed around the site to keep it dry, making it far easier to work than if the site were still submerged under the waters of the lagoon.

Most of the archaeological sites in the lagoon are in areas subject to regular flooding by the tides and so special technology is required, such as the use of pumps to remove water from the excavations. Since these sites are also often in anaerobic conditions (under water or below sediment), any organic materials are usually well preserved. This means that wooden piles and other structures are frequently discovered. On the down side, iron objects are far rarer owing to the strong acidity of such an environment.

A lot has been written about the origins of the lagoon, but the debate is still open. The most controversial issue is linked to environmental changes that have taken place over the past two millennia and which are largely the result of humankind’s intervention.

More specifically, people are still debating whether or not there were any Roman settlements in the area around Venice and, if they existed, whether these were dependent on or independent of the nearby town of Altinum .

In view of the recent discovery of sites dating back to the times of the Roman Empire and later centuries, it could now be argued that there were already certain facilities for inland navigation, presumably serving the river port of Altinum, at least from the 1st Century ad onwards. Roman anchors and shipwrecks found at the bocche di porto of "Malamocco" and "Lido" would confirm there were inland shipping routes leading from the sea to the mainland via the lagoon well before the Serenissima was founded.

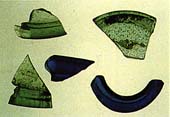

Structures called "arginali" are often found: these are long, narrow piles of amphorae (intact or in fragments) surrounded and restrained by wooden piles. We are still not exactly sure about their purpose: they might have been sea defences, alzaie or embankments with roads across the marshes.

It is always difficult to interpret finds with any great certainty on account of the difficulties faced when studying archaeological sites submerged in muddy waters and the problems of dating. In fact, the archaeologist’s most reliable dating system (the stratigraphic method) is particularly difficult to apply in this environment.

There is also much archaeological evidence from the Early Middle Ages and later periods in the lagoon area.

These are crucial for our understanding of the dynamics of how the city of Venice developed as well as other places trading towns and ports like Torcello and Malamocco.

Local archaeological sites give us an insight into the specific settlement techniques adopted in the lagoon area and how these towns and villages were supported and protected. These techniques included gradual strengthening of the banks along the canals and island shorelines in order to protect emerged areas and to reclaim further land from the water.

Originally, the settlers wove branches to create barriers, later switching to the use of wooden piles driven into the ground to support wooden fences and even banks of stone resting on wooden piles where necessary.

In recent years, much attention has also been turned to the subsoil of the old city centre, resulting in the discovery of many monuments that help enrich our knowledge of the urban development of Venice and the history of the Serenissima.

Thanks to controls during building work and planned archaeological excavations several previous building structures have been found under Venice’s palaces, plus ancient shorelines and public wells .

Many old churches (abolished in the Napoleonic era) with adjoining cemeteries have been found and other ecclesiastical structures most of which had also been suppressed during French occupation of the city.

In fact, Venice had a particularly large number of churches and monasteries and so these are one of the most evident aspects of archaeology in the city and the islands, nearly all of which could boast at least one monastery.

Archaeological studies of the lagoon area also make a major contribution to our knowledge of naval construction. The most famous discovery is, of course, that of a galley and a flat bottom boat later used as barriers to protect the shores of the island of San Marco in Boccalama from erosion, where there was a monastery in the early 14th Century. These ships were discovered and excavated during the construction of a solid barrier needed to dry the area. They have now been fully documented and await funds and planning for recovery and restoration

The San Marco in Boccalama galley is our only example of a well preserved and complete Middle Ages galley. The Venetian galley was a most formidable weapon of war for maritime cities in the Middle Ages, as well as an excellent merchant ship used for the precious cargo coming from trade in the East and with Britain responsible for Venice’s wealth and maritime power.

During construction of the mobile dams (the MOSE project), other wrecks have recently been found at the "Malamocco" and "Lido" port entrances. These date back to the 18th and 19th Centuries and are currently being excavated. The most interesting of these is an early eighteenth-century ship, probably of Venetian origin, that has produced several guns and numerous iron objects.

Another slightly older wreck, that of a boat off the island of Lido, is known as the “relitto dei mattoni” (wreck of bricks) due to its cargo of tiles.

It is easy to believe that these are not likely to be the last naval discoveries by Venetian archaeologists in view of Venice’s millennial maritime history and the Ancient Romans’ previous presence in the lagoon.

Carlo Beltrame